After three decades of sharp decline,

American Indians now have the lowest fertility rate of all ethnic groups in the

U.S. The trend is real and is not due to sub-fertile Whites self-identifying as

American Indians.

The

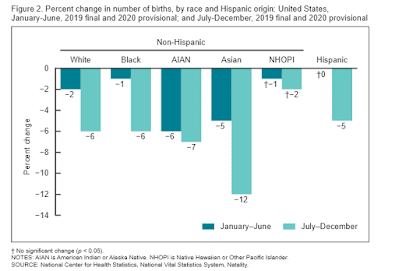

pandemic has reduced the American birth rate. According to data from 2020 and

early 2021, almost all ethnic groups have taken a hit, but the magnitude has

been greater for some than for others.

Asian Americans took the biggest hit. At first thought, this makes sense. Asians, especially East Asians (who make up a majority of Asian Americans) tend to take infectious diseases more seriously. They are generally more willing to wear masks, practice social distancing, and wash their hands, and it seems logical that they would also be more willing to postpone childbearing.

But

that's not the whole story. The pandemic has accelerated an ongoing fertility

decline among East Asians at home and abroad. With the exception of North Korea,

East Asia was already a zone of ultra-low fertility—about one child per woman.

When the pandemic is over, I predict that East Asian fertility will not return

to pre-pandemic levels. The decline will continue. The pandemic has merely

acted as a social accelerant (Frost 2020).

This view is strengthened if we return to the above graph and look at the group that took the second-biggest hit: American Indians and Alaskan Natives. Their fertility rate has likewise been declining. It was still high in the 1980s, but sometime around 1990 it began to plummet, falling below the fertility rate of any other ethnic group in the U.S. by the early 2000s.

What's

going on? Is the decline real? Or is it a statistical fluke? Perhaps

sub-fertile Whites are self-identifying as American Indians in growing numbers.

This hypothesis was tested by Cannon and Percheski (2017):

Concurrent with this decline in estimated TFRs, the self-identified AI/AN population enumerated in the decennial US Census increased in size, largely because of changes in the racial categories and in the wording of racial identity items on the census forms.

The increase in the census counts of the American Indian population means that there are several possible explanations for the decline in American Indian fertility rates published by Vital Statistics. First, the decline could be a mechanical artifact of differential changes in racial identification between the two data systems Vital Statistics used to calculate fertility rates. Second, the decline could be driven by compositional changes in who identifies as American Indian. Third, there may be real changes infertility behavior that are unrelated to changes in who identifies as American Indian.

To

control for these differences in definition and self-identification, Cannon and

Percheski (2017) used a single data system (the American Community Survey) for

the period 1980 to 2010. They also examined the fertility decline on the basis of

three definitions of American Indian/Alaskan native: 1) women who identify as

AI/AN only, 2) any woman who identifies as AI/AN, whether identifying one or

more races, and 3) women who list a specific tribe or American Indian for the

ancestry question. The second definition seems to be the one most vulnerable to

"ethnic reassignment."

Cannon

and Percheski (2017) found that all three definitions showed a fertility

decline, particularly the first one. The decline was steepest among younger

women. However, there was no indication that lower fertility at younger ages

was being offset by higher fertility at older ages. The authors concluded:

"This finding of declining TFRs estimated within a single data system is

evidence against the explanation that fertility declines are merely artifacts

of data collection changes or incongruences."

So

what is the explanation? The main cause seems to be the declining marriage

rate: "fertility rates among married and unmarried women have remained

fairly stable, while the share of women ever married has declined across birth

cohorts. Thus declines in fertility rates seem to be linked with changes in

marriage for this population."

In

this respect, American Indians are more vulnerable than most other ethnic

groups in the U.S. Their women seem to prefer having children when a man is in

the home. As the authors note, "other population subgroups in the United

States who have experienced substantial declines in marriage have not

experienced such drastic declines in fertility levels" (Cannon and

Percheski 2017, pp. 8-9).

Anthropologists

have long noted that the Indigenous peoples of the Americas still retain many

"Arctic" adaptations in their anatomy. Could the same be true for

their behavioral predispositions? Some 12,000 years ago, their ancestors lived

in northeast Asia and Beringia. In that environment, women had almost no food

autonomy and could not raise children on their own. Perhaps their female

descendants are still making a half-conscious link between having a baby and

having a male provider.

References

Cannon,

S., and C. Percheski. (2017). Fertility change in the American Indian and Alaska

Native population, 1980-2010. Demographic

Research 37: 1-12.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/26332188

Frost,

P. (2020). An Accelerant of Social Change? The Spanish Flu of 1918-19.

International Political Anthropology

Journal 13(2): 123-133.

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4295574

Hamilton,

B.E., M.J.K. Osterman, and J.A. Martin. (2021). Declines in births by month: United States, 2020. NVSS Vital Statistics

Rapid Release. Report no. 14, June

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr014-508.pdf