Occurrences of ‘Blumenbach’ in published writings.

After a peak in the early 19th century, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach faded into

the background. He had little influence on the thinking of later

anthropologists. (source)

Stephen Jay Gould believed that the Western world

view had been perverted by the racial theorizing of anthropologists in the 18th

and 19th centuries, one of them being the American anthropologist Samuel George

Morton (1799-1851). Another was his German contemporary Johann Friedrich

Blumenbach (1752-1840):

In the eighteenth century a

disastrous shift occurred in the way Westerners perceived races. The man

responsible was Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, one of the least racist thinkers

of his day.

[…] Blumenbach chose to regard

his own European variety as closest to the created ideal and then searched for

the subset of Europeans with greatest perfection--the highest of the high, so

to speak. As we have seen, he identified the people around Mount Caucasus as

the closest embodiments of the original ideal and proceeded to name the entire

European race for its finest representatives.

[…] however subjective (and even

risible) we view the criterion today, Blumenbach chose physical beauty as his

guide to ranking. He simply affirmed that Europeans were most beautiful, with

Caucasians as the most comely of all.

[…] Where would Hitler have been

without racism, Jefferson without liberty? Blumenbach lived as a cloistered

professor all his life, but his ideas have reverberated in ways that he never

could have anticipated, through our wars, our social upheavals, our sufferings,

and our hopes. (Gould, 1994)

As Gould himself noted, Blumenbach denied that human

populations differ in mental capacity. In this, he was less racist than many other

people of his day. But he did posit differences in sexual beauty, thus ultimately

leading humanity to … Hitler.

Is this true? Yes, Blumenbach considered Europeans the

most attractive of all humans, as we may see in his work De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa:

Caucasian

variety.

Colour white, cheeks rosy, hair brown or chestnut-coloured [...] In general,

that kind of appearance which, according to our opinion of symmetry, we

consider most handsome and becoming. (Blumenbach, 1795, p. 265)

Meiners refers all nations to two

stocks: (1) handsome, (2) ugly; the first white, the latter dark. He includes

in the handsome stock the Celts, Sarmatians, and oriental nations. The ugly

stock embraces all the rest of mankind. (Blumenbach, 1795, p. 268)

Caucasian

variety.

I have taken the name of this variety from Mount Caucasus, both because its

neighbourhood, and especially its southern slope, produces the most beautiful

race of men, I mean the Georgian; and because all physiological reasons

converge to this, that in that region, if anywhere, it seems we ought with the

greatest probability to place the autochthones of mankind. For in the first

place, that stock displays, as we have seen, the most beautiful form of the

skull, from which, as from a mean and primeval type, the others diverge by most

easy gradations on both sides to the two ultimate extremes (that is on the one

side, the Ethiopian, on the other, the Mongolian) […] (Blumenbach, 1795, p.

269)

These passages, however, covered less than a page

out of a tome that ran to 276 pages. Nor did they recount anything new in the

academic or popular literature. Blumenbach simply stated what most people

of his time believed, as is implied by the above quotes. One likeminded person

was the French naturalist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832):

The white race, with its oval

face, long hair, protruding nose, to which the civilized peoples of Europe

belong, and which appears to us to be the most beautiful of all races, is also

much superior to the others by strength of genius, courage and activity.

(Cuvier, 1798, p. 71)

Another was the American President Thomas

Jefferson (1743-1826):

And is this difference [of color]

of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty

in the two races? Are not the fine mixtures of red and white, the expressions

of every passion by greater or less suffusions of colour in the one, preferable

to that eternal monotony, which reigns in the countenances, that immoveable

veil of black which covers all the emotions of the other race? Add to these,

flowing hair, a more elegant symmetry of form, their own judgment in favour of

the whites, declared by their preference of them […] (Jefferson, 1785, p. 265)

Blumenbach did not create a perception that

Europeans were more beautiful than other humans. That perception already

existed.

Influences on

later anthropologists?

But was Blumenbach instrumental in transmitting this

perception to later anthropologists? Did he play a pivotal role in creating the

racialized mind-set of later times? That, too, is doubtful. There is a chasm

between him and his successors. Unlike the latter, he saw human diversity

through the lens of the Bible, in particular the story of the Flood. Since

Noah’s Ark came to rest on Mount Ararat, he reasoned that the inhabitants of

that region must closely resemble the humans that God chose to repeople the

Earth. From this epicenter of physical perfection, Noah’s descendants spread to

other lands and gradually became less perfect in appearance.

This view is quite unlike later ones, which were

framed in secular and evolutionary terms. For Blumenbach, change was

degenerative, moving from the perfect to the less perfect. Later

anthropologists, while accepting the possibility of degenerative change, saw a

general trend towards advancement and increasing complexity.

Like others of his time, Blumenbach also believed in

the inheritance of acquired characteristics. If people of any origin share the

same climate, diet, and means of existence, they will converge to the same

physical type—not through natural selection, but through the direct action of

the environment. In this, he was poles apart from later writers, particularly

those influenced by Charles Darwin and Gregor Mendel.

The chasm between him and later writers can be seen

in the occurrence of the term ‘Blumenbach’ in books over the years. After a

peak in the early 19th century, references to his name fell into steep decline,

long before the publication of Darwin’s Descent

of Man in 1871 (Hawks, 2013). That book had only four such references, all

of them minor.

Finally, European writers do not assign this German

naturalist a key role in the development of racial thinking. In a recent French

dictionary on the history of racism, there are entries for such individuals as

Bolk, Buffon, Darwin, Gobineau, Haeckel, Nietzsche, and Linnaeus, but none at

all for Blumenbach (Taguieff, 2013).

Famous but no

real legacy

Blumenbach, though widely respected in his time, made

few intellectual contributions that would be both lasting and original, other

than his coining of the term ‘Caucasian’ for white folks. What about the notion

that the Caucasus is the epicenter of human beauty? It was already in

circulation, as seen in this passage by the French traveler Jean Chardin

(1643-1713):

[…] the Persian blood is now

highly refined by frequent intermixtures with the Georgians and the

Circassians, two nations which surpass all the world in personal beauty. There

is hardly a man of rank in Persia who is not born of a Georgian or Circassian

mother; and even the king himself is commonly sprung, on the female side, from

one or other of these countries. As it is long since this mixture commenced,

the Persian women have become very handsome and beautiful, though they do not

rival the ladies of Georgia (Lawrence, 1848, p. 310)

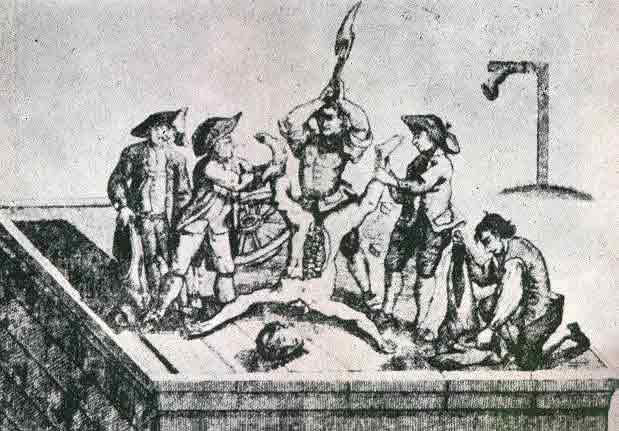

The Caucasus was the last area where one could

freely buy fair-skinned women for marriage or concubinage, typically for

clients in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia. Previously, the zone

of recruitment had been larger, extending into what is now Ukraine and southern

Russia. Further back in time, it had covered almost all of Europe. But this earlier

page of European history was largely forgotten by Blumenbach’s time.

Blumenbach really had only one original idea. He saw

a causal link between the biblical account of the Flood and the beauty of

European women, particularly those from the Caucasus. But that single flash of

insight would leave no lasting impression on future generations.

More shenanigans

…

None of this was pointed out in 1994, when Stephen

Jay Gould published his essay on Blumenbach. Or perhaps it was. If a man shouts

in a forest and no one listens, did he ever really say anything?

Two years later, Gould incorporated this essay into

a new edition of The Mismeasure of Man.

Once again, he couldn’t resist the urge to “fudge”:

In 1996, when Gould updated The Mismeasure of Man, he added an

article about Blumenbach. It included a drawing of skulls which Gould claimed

to be an illustration from one of Blumenbach’s books. In this graphic, a

Caucasian skull is situated higher than those of other races. When a paper by

University of Tubingen historian Thomas Junker demonstrated that the original

drawing placed all the skulls at the same level, Gould blamed the mistake on

his editor saying, “I don’t think that I even knew about the figure when I

wrote the article, for I worked from a photocopy of Blumenbach’s text alone.”

Gould dismissed this error as “inconsequential” and faulted Junker for

misstating “the central thesis of my article—a misinterpretation that cannot, I

think, be attributed to any lack of clarity on my part.” (Michael, 2013)

One might wonder why Gould missed this error when he

got the galley proofs for the new edition. Furthermore, since his errors point

in the same direction, one might wonder whether there had been a systematic

tendency to distort the facts, either consciously or unconsciously. Wasn’t this

the same argument he had made when condemning Samuel George Morton?

References

Blumenbach, J.F. (1795). De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa, trans. On the Natural Variety of Mankind, 1865, London.

Cuvier, G. (1798). Tableau

elementaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux, Paris.

Gould, S.J. (1994). The Geometer of Race, Discover Magazine, (November 1994),

online edition

http://discovermagazine.com/1994/nov/thegeometerofrac441#.UOGEqXcdOZQ

Jefferson, T. (1785). Notes on the State of Virginia,

http://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=JefVirg.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=14&division=div1

Hawks, J. (2013). Blumenbach, Haeckel, Dobzhansky,

January 2, John Hawks Weblog,

http://johnhawks.net/weblog/topics/history/biology/blumenbach-haeckel-dobzhansky-2013.html

Lawrence, W. (1848). Lectures on Comparative Anatomy, Physiology, Zoology, and the Natural

History of Man, London: Henry G. Bohn.

Michael, J.S. (2013). Stephen Jay Gould and Samuel

George Morton: A Personal Commentary, Part 4, June. 14, Michael1988.com

http://michael1988.com/?p=203

Taguieff, P.-A. (ed.) (2013). Dictionnaire historique et critique du racisme, Paris: Presses

Universitaires de France.