skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Japan

is robotizing not only manufacturing but also the service sector (Wikicommons -

Michael Ocampo)

In

my last two posts I argued that South Korea has embraced not only ultra-low

fertility but also mass immigration. In this, it has more in common with

Western Europe and North America than with neighboring China and Japan.

China

is out of step with Western immigration policy for understandable reasons: it

is only now exhausting its reserves of cheap labor and, furthermore, has

problematic relations with the West. But those reasons hardly apply to Japan—a

Western ally with fewer and fewer people of working age. Yet that country has

been going its own way on immigration, just as it has in other areas, notably

automation and robotization. In the

West, robotics research is a low priority, except for military applications. In

Japan, it is a high priority and has the stated aim of staving off immigration:

"Japan's

push for automation has historically been driven by political and social

resistance to large-scale immigration by non-Japanese, rooted in the idea that

there would be a deep cultural incompatibility with such immigrants," says

Grant Otsuki, a lecturer in cultural anthropology at Victoria University of

Wellington.

"In

contrast, robots are generally seen as compatible with tradition and culture,

or at least 'neutral', and therefore more acceptable than immigrants."

(Townsend 2019)

Robotic

beings have a good image in Japan, as shown by a spate of movies where a shy

boy falls in love with a female android: Chobits

(2002), Cyborg She (2008), and Q10 (2010). In contrast, we see a darker

image in Western movies, such as the Terminator

series, Ex Machina (2015), and Blade Runner (1982 and 2017).

Keep

in mind that culture is upstream from policy. If you think movies are made only

to provide entertainment, you probably also believe that newspapers serve only

to cover the news and that advertisements are used only to sell a specific good

or service. Culture is an effective way to shape future policies.

South Korea and

Japan: different responses to the same demographic crisis

The South Korean

response

Although

South Korea and Japan face the same demographic crisis, i.e., an aging society

and a low birth rate, they have responded in very different ways. South Korea

has greatly liberalized its immigration policy, both in law and in enforcement

of the law. Since 1997 the country has opened up its labor market to guest

workers and has relaxed enforcement to the point that half of all migrants are

undocumented (Moon 2010).

Song

(undated) sees a link between the beginning of large-scale labor immigration to

his country and the IMF bailout of 1997. However, the "Memorandum on the

Economic Program," written by the South Korean government in response to

the IMF, says nothing specific about immigration. There is only a promise to

implement "labor market reform" and take "further steps to

improve labor market flexibility" (IMF 1997). Perhaps other promises were

made off the record.

To

gain support for large-scale immigration, the government began to promote

multiculturalism from 2006 onward:

But

the South Korean media also began to host fervent discussions of

multiculturalism. In 2005-2006, the number of articles on the topic tripled

from previous years. The media shift was echoed by a change in policy from the

top, initially driven by President Roh Moo-hyun. The campaign then crossed

ministerial divisions and party lines, surviving the changeover from the

liberal Roh administration of 2003-2008 to the more conservative administration

of President Lee Myung-bak. Lee's government sought both to persuade the public

to embrace immigrants and to promote integration by educating new foreign-born

brides in the intricacies of Korean culture. The Ministry of Gender Equality

and Family simultaneously started a campaign to persuade the public to accept

multiculturalism. Immigration commissioners and the presidential committee on

aging set multiculturalism as a national priority to combat a maturing society.

South Korea was to become a "first-class nation, with foreigners" — a

phrase echoed throughout government documents and speeches. (Palmer and Park

2018)

Watson

(2010) ascribes this new policy to the neo-liberalism that has dominated both

the Right and the Left, particularly since the IMF bailout of 1997:

For

the conservative government, South Korean nationalism and democracy is

fundamentally tied to the doctrine of neo-liberalism. Neo-liberalism refers to

the flow of economic migrant labour and mobile global capital. This global

environment also requires government policies to attract foreign migrants and

workers into South Korea's economy and society.

Multiculturalism

is a state-led response to these global changes. The policies of

multiculturalism define the present and future economic, security and cultural

national strength of South Korea. Critics suggest that, in fact, the GNP

regards multiculturalism as an instrumental policy of increasing national state

power in this global environment. (Watson, 2010)

The

GNP is the Grand National Party. It dominates the political right and resembles

mainstream Republicanism in the United States:

The Japanese

response

Meanwhile,

Japan has been much less willing to open its borders, despite being East Asia's

primary destination for foreigners. Its illegal immigrant population has actually

declined through stronger law enforcement, and legal immigrants have been

mostly overseas Japanese from Latin America. Last year, however, its parliament

passed a law to bring in foreign workers for jobs in construction, agriculture,

the hotel industry, cleaning, and elder care. Initially, 500,000 were slated to

come over the next five years, but the total was cut to 345,000 (Denyer 2018;

Nikkei 2018; Shigeta 2018).

Those

numbers are still much lower than the 2.4 million foreign workers currently in

South Korea, a much smaller country in size and population. In addition,

Japan's guest workers will be paid the same as Japanese doing the same work

(Denyer 2018). This is in stark contrast to South Korea, which has the largest

wage gap between local and immigrant labor in the OECD (Hyun-ju 2015).

Japan

is still criticized for not opening up enough. One example is this Washington Post article, whose author

warns the U.S. against becoming another Japan:

Now,

to be clear, Japan is a wondrous nation, with an ancient, complex culture,

welcoming people, innovative industry — a great deal to teach the world. But

Japan also is a country that admits few immigrants — and, as a result, it is an

aging, shrinking nation. By 2030, more than half the country will be over age

50. By 2050 there will be more than three times as many old people (65 and

over) as children (14 and under). Already, deaths substantially outnumber

births. Its population of 127 million is forecast to shrink by a third over the

next half-century. (Hiatt 2018)

Robotization

may make life easier for Japan's growing numbers of elderly but will it pay for

their pensions? Mind you, the same sort of question could be asked about

low-wage immigration to the U.S.

Why is Japan so different?

A

key reason seems to be a high degree of cultural autonomy and a correspondingly

high degree of cultural isolation. The term "isolation" might seem

strange for a country that does so much importing and exporting. Nonetheless,

manufactured goods are not the same as beliefs. The latter are distributed not

via shipping containers but through shared language and through shared

discourse spaces in academia, entertainment, and the media.

Poor knowledge of

English

English

has become the language of globalism, and knowledge of English correlates

worldwide with public acceptance of core globalist beliefs. In Japan, English

is not widely used or understood, even among the well-educated:

Although

English is a compulsory subject in junior high and high school in this country,

Japanese still have a hard time achieving even daily conversation levels.

According to the most recent EF English Proficiency Index, the English level of

Japanese is ranked 35th out of 72 countries. The top three are the Netherlands,

Denmark and Sweden, which are all northern European nations. Among Asian

countries, Singapore is placed sixth, Malaysia 12th, the Philippines 13th,

India 22nd and South Korea 29th. Japan places between Russia and Uruguay.

(Tsuboya-Newell 2017)

Sullivan

and Schatz (2009) found that attitudes toward learning English correlated

negatively with patriotism (defined as positive identification and affective

attachment to one's country) and positively with nationalism, internationalism,

and pro-U.S. attitudes. Here, "nationalism" is defined as

"perceptions of national superiority and support for national

dominance"—what Steve Sailer has dubbed "Invade the world, invite the

world!"

Relative isolation

of academia

Academia

can propagate a new discourse in several ways:

-

by inculcating it in young adults

-

by acting as a trusted gatekeeper that serves to distinguish between

"correct" and "incorrect" discourse.

-

by mobilizing scarce intellectual resources for the development and

dissemination of "correct" discourse.

New

forms of discourse, like globalism, cannot easily penetrate Japanese colleges

and universities by means of overseas-trained leaders. Unlike the case in many

other Asian countries, educational authorities prefer to select future leaders

from within, attaching little importance to foreign experience and credentials

for promotion within the system (Yonezawa et al. 2018, p. 235). Foreign-born

professors are hired mostly for teaching English language and literature.

Relative isolation

of policy makers

This

relative isolation is true for Japanese in general, including policy makers.

International organizations, like the IMF, have little input into public

policy, in large part because Japan's debt is almost wholly Japanese-owned.

This economic independence has been a longstanding characteristic of Japan and

enjoys support not only from the political left but also from the political

right:

In

Japan, unlike many of the social democracies resisting capital movements, the

most important political opposition came not from organized labor and a

political Left anxious to prevent capital flight and to protect the welfare

state; rather, it came from nominally "conservative" politicians;

many bureaucratic agencies, including the MOF; and protected, cartelized

sectors of the economy, including banks, securities houses, and insurance

firms. (Pempel 1999, p. 911)

In

the West, globalism coopted first the Right and then the Left. That process is

still at an early stage in Japan.

Conclusion

I

would like to conclude with three points:

-

Japan will be a nice place to visit during the troubled 2020s. The same decade

will see South Korea become more and more like the West, especially the United

States—in keeping with stated policy goals.

-

English is the language not only of globalism but also of anti-globalism. Just

as Japan will move toward globalism more slowly than the West, it will also

move away more slowly ... when that time comes. As for South Korea, it will

enter a period of polarization, perhaps violent polarization.

-

Japan shows that the Western model of modernity is not the only one, or even

the best. The Western model is a product of specific circumstances,

particularly the presence of a large rentier class that feeds on growth while

doing little to make growth sustainable. At home and abroad, our rentier class

continually pushes for high rates of growth through expansion of the money

supply, through mass immigration, and through rapid exploitation of resources

that are either non-renewable or slowly renewable.

Japan's

slow-growth model is problematic in other ways, but it promises to be more

sustainable in the long run.

References

Denyer,

S. (2018). Japan passes controversial new immigration bill to attract foreign

workers. The Washington Post.

December 7

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/japan-passes-controversial-new-immigration-bill-to-attract-foreign-workers/2018/12/07/a76d8420-f9f3-11e8-863a-8972120646e0_story.html

Hiatt,

F. (2018). Anti-immigration Republicans have a decision to make about America's

future. Washington Post January 2018

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/without-immigration-america-will-stagnate/2018/01/28/e659aa94-02d5-11e8-8acf-ad2991367d9d_story.html

Hyun-ju.

(2015). Korea's wage gap between local, foreign workers largest in OECD. The Korea Herald, September 9

http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20150909001162

IMF

(1997). Memorandum on the Economic

Program. December 3.

https://www.imf.org/external/np/loi/120397.htm#memo

Moon,

S. (2010). Multicultural and Global Citizenship in the Transnational Age: The

Case of South Korea. International

Journal of Multicultural Education 12: 1-15.

https://ijme-journal.org/index.php/ijme/article/view/261

Nikkei

(2018). Abe vows to bring in more foreign workers. Nikkei Asian Review. June.

https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Abe-vows-to-bring-in-more-foreign-workers

Palmer,

J., and G.-Y. Park. (2018). South Koreans learn to love the Other. How to

manufacture multiculturalism. Foreign

Policy. July 16

https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/07/16/south-koreans-learn-to-love-the-other-multiculturalism/

Park,

Y-B. (2017). South Korea Carefully Tests the Waters on Immigration, With a

Focus on Temporary Workers. Migration

Policy Institute, March 1

https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/south-korea-carefully-tests-waters-immigration-focus-temporary-workers

Pempel,

T.J. (1999). Structural Gaiatsu: International Finance and Political Change in

Japan. Comparative Political Studies 32:

907-932.

Shigeta,

S. (2018). How Japan came around on foreign workers. Nikkei Asian Review, June.

https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/How-Japan-came-around-on-foreign-workers

Song,

H-J. (undated). Immigration Policy in

South Korea & Japan - A Comparative Perspective Theoretical framework.

University of Tsukuba. International and Advanced Japanese Studies. PowerPoint

presentation

http://japan.tsukuba.ac.jp/09225Song.pdf

Sullivan,

N. and R.T. Schatz (2009). Effects of Japanese national identification on

attitudes toward learning English and self-assessed English proficiency. International Journal of Intercultural

Relations 33(6): 486-497

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0147176709000236

Townsend,

R. (2019). Japan's big dilemma: robots or immigrants? Asia Media Centre. March 1

https://www.asiamediacentre.org.nz/features/japans-big-dilemma-robots-or-immigrants/

Tsuboya-

Newell, I. (2017). Why do Japanese have trouble learning English? The Japan Times, October 29

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2017/10/29/commentary/japan-commentary/japanese-trouble-learning-english/#.XWK2DHdFzct

Watson,

I. (2010). Multiculturalism in South Korea: A Critical Assessment. Journal of Contemporary Asia 40:

337-346.

Yonezawa,

A., Y. Kitamura, B. Yamamoto, and T. Tokunaga. (2018). Japanese Education in a Global Age. Sociological Reflections and Future

Directions. Springer.

https://books.google.ca/books?id=shdnDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=fr&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

By

mid-century, immigrant workers will be almost as numerous as native-born

workers (AINZ 2016)

Readers

took exception to a population forecast in my last post: children of mixed

parentage will make up a third of all South Korean births in 2020 (Lim 2011).

Yet in 2015 they made up only 5% (Lim 2017). From 5% to one third—is that

possible in only five years?

This

forecast was tangential to my argument. Ultimately, the rate of population

replacement is less important than the final outcome. All the same, this

forecast seems to me plausible because South Korea's population is changing at

an accelerating rate. There are three interacting reasons:

Logarithmic

increase

The

increase in births of "multicultural children" is logarithmic, and

not linear. In 2015, such children numbered 207,693 and more than half were

under 6 years of age (Wiki- Multicultural Family in South Korea 2019). This

factor, alone, will cause the annual number of such births to double or even

triple between 2015 and 2020.

Declining

fertility of native-born women

The

total fertility rate declined from 1.25 births per woman in 2015 to 0.98 in

2018 (Steger 2019). The rate of decline is probably higher for native-born

women. In addition, fewer of them are of childbearing age. These two factors

are together driving down the total number of births. In one year alone, from

2017 to 2018, the birth rate fell by 8.6% (Steger 2019).

Shift in sources

of foreign brides toward high-fertility countries

Initially,

many foreign brides were ethnic Koreans from northeast China, where the total

fertility rate is even lower, only 0.75 births per woman (Wang 2018). The

ethnic mix is now shifting toward brides from Southeast Asia, where TFRs are

three or four times higher: Philippines: 3 births per woman, Vietnam: 2 births

per women, Indonesia: 2.1 births per woman, Cambodia 2.5 births per woman.

So

will "multicultural children" make up 33% of all births in 2020?

Forecasts can be wrong, but I don't think this one will be far off the mark. On

the one hand, the annual number of such births seems to be more than doubling

every five years. On the other hand, the total number of South Korean births is

falling sharply.

By the way, that

forecast doesn't include labor immigration

Please

note: this is not the whole story of population replacement in South Korea.

There is also labor immigration, which will become more and more important

demographically:

[...]

The government has brought in an immigration policy that actively embraces

immigrants. Last year, it formulated it in the low birth rate and aging

measures and economic policy direction. It will actively accept immigration and

solve various economic and social problems such as lack of population.

Immigration policy will be in full swing after 2018.

[...]

According to the data from the Korea Immigration Policy Institute, a steady

influx of immigrants is needed to increase the potential growth rate by 1

percentage point. In 2020, there will be 4,994,000, and in 2030, 9,927,000. In

2035, 10,864,000 people will be needed, a quarter of the total working

population of 41.75 million. In 2050, 16,116,000 people will be needed. In

2060, there will be 17,224,000 people—only 4 million people less than the

domestic workforce (21,865,000 people). (AINZ 2016)

It’s

not clear whether these immigrants and their children will be entitled to

citizenship or will always be guest workers. In the end it doesn’t really

matter. They will become a permanent presence in South Korea.

Can South Korea

overcome its fertility crisis?

Fertility

rates can rise, just as they can fall, as one commenter noted:

[...]

there's no reason to think native Korean fertility is going to stay at such a

low level indefinitely. Birth rates go up and down and yearly TFRs are just a

snapshot. A number of European countries had fertility drop to very low levels

and have seen their TFRs increase significantly, though usually not to

replacement. Czech Republic, Romania, Russia and Georgia all come to mind.

(Georgia's fertility is now at replacement actually, thanks to their church.) I

could see South Korean fertility following that pattern.

Yes,

fertility rates can rise, but vigorous action is needed to make them rise. I'm

not convinced that such action will be sufficient in South Korea's case.

Detailed analysis suggests that the fertility rate is so low because many young

adults are trapped in "nonregular" jobs that offer little stability

and no benefits, particularly maternity or parental leave. They are nonetheless

expected to meet traditional preconditions for family formation:

Our

analysis also indicates a very limited scope for future fertility increase in

Korea, especially because larger families have almost vanished. [...] The low

fertility will be sustained by irregular work contracts among younger people

and a combination of unfavorable labor market conditions for women with

families and the persistence of traditional gender roles and expectations

regarding their family roles, household tasks, caring for dependent members,

and childrearing. (Yoo and Sobotka 2018)

The

example of South Korea suggests that social conservatives may be wrong in blaming

the West's fertility crisis largely on the decline in traditional values and

the rise of alternative sexual lifestyles (single motherhood, gay marriage,

etc.). These factors are much less important in South Korea. Furthermore, an

argument can be made that some traditional values are doing more harm than good

in the current economic environment, both in South Korea and in the West,

specifically the idea that parents shouldn't start a family until one of them

has secure employment. In most cases, that precondition will never be met.

The

main problem is thus twofold: 1) young adults increasingly have precarious

employment and are postponing childbearing until their situation becomes

sufficiently stable; 2) the culture in general has shifted away from the family

and toward employment as the ultimate meaning of life.

Young

South Koreans should explore alternative means of gaining income and accept the

idea that family life can be just as rewarding as work life. This will be difficult

to do, however, if the South Korean government pursues its commitment to

globalism. Young adults are increasingly thrown into competition with poorly

paid foreign workers, either through outsourcing of employment to low-wage

countries or through insourcing of low-wage workers for "3D jobs"—dirty,

dangerous, and demeaning (Mundy 2013).

Employers

are in fact incentivized to bring in foreign workers. South Korea has the

largest wage gap of OECD countries between local and immigrant labor, and the

gap remains even when one controls for differences in work skills (Hyun-ju

2015). This use of immigrants to do "work that Koreans won't do" has

the perverse effect of increasing such employment while reducing employment

that can support a family.

References

AINZ (2016).

Population in 2750 South Korea, large-scale immigration government in progress.

January 9

https://issuecollecter.tistory.com/178

Hyun-ju.

(2015). Korea's wage gap between local, foreign workers largest in OECD. The Korea Herald, September 9

http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20150909001162

Lim,

T. (2011). Korea's multicultural future? The

Diplomat, July 20

https://thediplomat.com/2011/07/south-koreas-multiethnic-future/

Lim,

T. (2017). The road to multiculturalism in South Korea. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, October 10

https://www.georgetownjournalofinternationalaffairs.org/online-edition/2017/10/10/the-road-to-multiculturalism-in-south-korea

Mundy,

S. (2013). S Korea struggles to take in foreign workers. Financial Times, September 17

https://www.ft.com/content/afcdefd4-1c1c-11e3-b678-00144feab7de

Steger,

I. (2019). South Korea's birth rate just crashed to another alarming low. Quartz Daily Briefs, February 27

https://qz.com/1556910/south-koreas-birth-rate-just-crashed-to-another-alarming-low/

Wang,

M. (2018). For Whom the Bell Tolls: A

Retrospective and Predictive Study of Fertility Rates in China (November 8,

2018). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3234861

Wikipedia (2019).

Multicultural Family in South Korea.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multicultural_family_in_South_Korea

Yoo,

S.H. and T. Sobotka. (2018). Ultra-low fertility in South Korea: The role of

the tempo effect. Demographic Research

38(22): 549-576.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/26457056.pdf?acceptTC=true&coverpage=false

Mid-term exams at a South

Korean middle school (Wikicommons - Samuel Orchard)

South Korea opened up to

mail-order brides a quarter of a century ago. Most are from Southeast Asia

(Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Indonesia), although some are ethnic

Koreans from northeast China. Men outnumber women in South Korea, as they do elsewhere in

East Asia, and the male surplus is even larger in rural areas because of the

many women who move to cities for employment (Park 2011).

As a result, 472,390

"multicultural marriages" were performed between 2000 and 2016 (Lim

2017). In 2005, the peak year, 13% of all marriages involved a foreign-born

bride. This way of finding a bride has been especially popular in rural areas,

where 40% of all couples are mixed (Park 2011). The offspring of these

marriages "are expected to number over 1.6 million by 2020, with a third

of all children born that year the offspring of international unions" (Lim

2011). In rural areas, this proportion is expected to be half of all children

by 2020 (Park 2011).

Such children will increase

both in absolute numbers and proportionately for three reasons. First, they are

born mostly in rural areas, where incentives for childbearing are relatively high.

Second, their mothers come from cultures where fertility is likewise relatively

high. Third, Korean women have a very low fertility rate: only 0.98 children

per woman in 2018.

South Korea is thus on track

for rapid demographic replacement. This change is interesting not only because

of its rapidity but also because it is happening in a country that differs

considerably from Western Europe and North America in history and culture.

Negative effects cannot be blamed on slavery, colonialism, or other chickens

coming home to roost. Until the twentieth century the country kept to itself, to

such a point that it was called "The Hermit Kingdom." There then

followed Japanese rule, American occupation, and devastating war. Not until the

1980s did South Korea become truly advanced, and affluent.

So can South Korea change its

population and remain advanced and affluent? This question is all the more

relevant because the country has only one natural advantage in the global

marketplace: its human capital.

Academic failure

In general, children of mixed

parentage do badly at school: "The drop-out rate among mixed-blood youths

is estimated at 9.4% in elementary schools and 17.5% at the secondary level,

compared with less than 3% among ordinary Korean youths" (Kang 2010).

This poor performance is

usually put down to the mother's poor language skills. "Because their

mothers have difficulty in speaking and writing Korean, these children may be

making slow progress in language development in comparison to the Korean

children" (Kang 2010). If this explanation is correct, such children

should do worse in subjects that demand much social interaction and language

use. Conversely, they should do better in subjects that require abstract

skills, like mathematics, or memorization of names and dates, like social

studies. This is, in fact, the pattern we see in children of East Asian

immigrants in North America.

But this is not the pattern we

see in children born in South Korea to non-Korean mothers: "Their

favourite subjects are music/painting/physical education (42.6%), while they

dislike math (38.1%), social studies (19.2%) and Korean (12.7%)" (Kang

2010). The learning deficit seems to be strongest in those subjects that

require the most abstraction and memorization.

Moreover, a study conducted

over several months found that these children do not have language problems

that can be traced to deficient learning at home from their mothers: "This

study revealed that multicultural children did not exhibit any difficulty in

communicating with others in everyday Korean but that they had varying degrees

of academic vocabulary mastery" (Shin 2018). So the problem is

not with learning of normal spoken language at home but with learning of

specialized terminology at school. The study's author concluded: “This finding

then raises the questions of why the simplified discourse about multicultural

children's deficiency in Korean has been easily accepted as true in society and

who benefits from the (re)production of the idea that they need special care,

particularly regarding Korean language instruction” (Shin 2018).

Non-compliance with social rules

Koreans are expected to show a

high level of compliance with social rules. These rules may apply to everyone

(e.g., wearing seatbelts) or only to students (e.g., no smoking, mandatory hand

washing). Compliance seems to be weaker in children of foreign-born mothers,

as suggested by lower rates of hand washing and wearing of seatbelts and higher

rates of smoking (Yi and Kim 2017).

Suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts

Children of mixed parentage

are more likely to contemplate and attempt suicide, but this seems to be

related more to decreased self-control than to increased depression or stress.

Kim et al. (2015) concluded: "There was no significant difference in the

levels of depression, self-reported happiness, and self-reported stress between

adolescents from multicultural and monocultural families. However, suicidal

ideation and suicidal attempt were significantly higher in adolescents from

multicultural families."

Violence and hyperactivity

Children of mixed parentage

also show higher levels of hostility, fear, anxiety, and anger (Moon and An

2011). Between the ages of 5 and 12 years they are more likely to engage in

hyperactive behaviors, as rated by their teachers (Park and Nam 2010). Finally,

between the ages of 11 and 13 years they are more prone to delinquency and

aggression (Lee et al. 2018).

On the other hand, Yu and Kim

(2015) found higher incidences of violence at school and non-compliance with

rules (smoking, drug use, alcohol use, sexual activity) only in children of foreign-born fathers and native-born mothers. Children of foreign-born

mothers and native-born fathers were behaviorally similar to children of native-born mothers and native-born fathers. It is true that the other studies lump

all “multicultural” children together, making no distinction between those with

foreign-born mothers and those with foreign-born fathers. However, the second

group is much smaller than the first—too small to explain the differing results.

This may be seen in the study by Yu and Kim (2015), which had 88 binational children of foreign-born fathers versus 622 of foreign-born mothers.

The findings of Yu and Kim

(2015) also run counter to the standard acculturation model. A child normally

has a stronger bond with its mother than with its father, so a child should

better assimilate Korean behavioral norms if its mother is Korean than if its

mother is non-Korean. But here we see the reverse.

Conclusion

The most robust finding is

that children of mixed parentage do poorly at school. The reason is commonly

said to be poor language skills, yet the pattern of academic failure is

actually the opposite of what that explanation would predict. Moreover, these children

seem to have no trouble with everyday spoken Korean. Their problem is with

specialized vocabulary that is normally learned at school and not at home.

Children of mixed parentage also

seem to be less compliant with rules and more prone to violence and

hyperactivity. This was the finding of three out of four studies. The

underlying cause may be weaker mechanisms for self-control, self-discipline,

and internalization of social rules. This factor may also play a role in the higher

incidences of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts.

In the academic literature, these

findings are explained in terms of normal versus abnormal development. Children

of mixed parentage are said to develop abnormally because they are more

interested in music and physical education than in math. Their higher levels of

violence and hyperactivity are explained the same way. But what if they had been assessed in their

mothers' home countries? Would they still seem so abnormal? On a global level,

few societies expect the degree of academic nerdiness that Koreans expect of

themselves.

Better research is needed. My

first suggestion: provide data on ethnicity. It’s not enough to distinguish

between "native-born" and "foreign-born." A foreign-born

mother could be an ethnic Korean from China who has more in common with a

native-born mother. There may also be significant behavioral differences among

binational children depending on which Southeast Asian country the mother comes

from. The relevant factor is really ethnicity and not place of birth.

This factor may explain why

children are less violent when they have foreign mothers and Korean fathers

than when they have Korean mothers and foreign fathers. The foreigners are

ethnically different in the two cases. In the first case, they are Southeast

Asians. In the second case, they are either U.S. servicemen or migrant laborers

who come not only from Southeast Asia but also from South Asia, Southwest Asia,

and Africa.

My second suggestion: do not

frame the issue solely in terms of "acculturation." i.e.,

insufficient learning by children of Korean culture, particularly the Korean

language. This is not to say that acculturation is never a causal factor, but

rather that it is assumed to be the only one, even to the point of

misrepresenting reality.

Yes, culture does matter, but

it interacts with other factors, including genetic ones. Humans everywhere have

had to adapt to their cultural environment—more so, in fact, than to their

natural environment—and this has been no less true for the Korean people. To

survive in a highly complex and demanding culture, they have had to acquire

certain mental capabilities:

- high cognitive ability (mean

IQ of 106)

- high self-control

- high degree of compliance

with social rules

- low time preference and,

correspondingly, strong future-oriented thinking

- strong inhibition of

violence, which can be released only if permitted by social rules

All of these mental capabilities

have moderate to high heritability and are no less real than the more visible

aspects of the human body, like gender, skin color, and body height. They exist

because they have enabled Koreans to survive and flourish in a specific

cultural environment

The Korean people have

achieved a high standard of living through their knowledge, foresight, and

self-discipline—qualities that are the outcome of a long process of

gene-culture coevolution. Generation after generation of their ancestors have had

to adapt to the demands of a harsh cultural environment, this adaptation being bought

at a high price: the success of some individuals and the failure of many more. This

is why Koreans traditionally revere their ancestors.

All of this has been gained

through much effort over many generations, but it can all be lost in one or

two. To do or to undo—which do you think is easier?

References

Kang, S.W. (2010).

Multicultural education and the rights to education of migrant children in

South Korea. Educational Review

62(3): 287-300.

https://books.google.ca/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=sgnKAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA37&ots=IcekxniSRj&sig=vQ-YWHSlouQuzFor5zP9OOkucsg#v=onepage&q&f=false

Kim, J-M., B-G. Kong, J-W.

Kang, J.-J. Moon, D.-W. Jeon, E.-C. Kang, H.-B. Ju, Y.-H. Lee, and D.-U. Jung.

(2015). Comparative Study of Adolescents' Mental Health between Multicultural

Family and Monocultural Family in Korea. Journal

of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 26(4): 279-287.

https://www.e-sciencecentral.org/articles/SC000022127

Lee, J.S., J.M. Kim, and A.R.

Ju. (2018). A structural analysis on the effects of children's parentification

in multicultural families on their psychological maladjustment - comparison

with children in monocultural families. Journal

of the Korea Institute of Youth Facility and Environment 16:117-130.

https://www.earticle.net/Article/A329970

Lim, T. (2011). Korea's

multicultural future? The Diplomat,

July 20

https://thediplomat.com/2011/07/south-koreas-multiethnic-future/

Lim, T. (2017). The road to

multiculturalism in South Korea. Georgetown

Journal of International Affairs, October 10

https://www.georgetownjournalofinternationalaffairs.org/online-edition/2017/10/10/the-road-to-multiculturalism-in-south-korea

Moon SH, and H.J. An (2011).

Anger, anger expression, mental health and psychosomatic symptoms of children

in multi-cultural families. Journal of

Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 20(4): 325-333.

https://synapse.koreamed.org/DOIx.php?id=10.12934/jkpmhn.2011.20.4.325

Park, S. (2011). Korean

Multiculturalism and the Marriage Squeeze. Contexts

10: 64-65.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1536504211418459

Park, J.H., and J.S. Nam

(2010). The language development and psychosocial adjustment of multicultural

children. Studies on Korean Youth. 21:129-152.

Yi, Y., and J-S. Kim. (2017).

Korean Adolescents' Health Behavior and Psychological Status according to Their

Mother's Nationality. Osong Public Health

and Research Perspectives 8(6): 377-383.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5749486/

Shin, J. (2018). Minority

youth's mastery of academic vocabulary and its implications for their

educational achievements: the case of 'multicultural adolescents' in South

Korea. Multicultural Education Review

10(1): 35-51,

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/2005615X.2018.1423539

Yu, J-O, and M. Sung Kim.

(2015). A Study on the Health Risk Behaviors of Adolescents from Multicultural

Families according to the Parents' Migration Background. Journal of Korean Academy of Community Health Nursing 26(3):190-198

https://synapse.koreamed.org/DOIx.php?id=10.12799/jkachn.2015.26.3.190

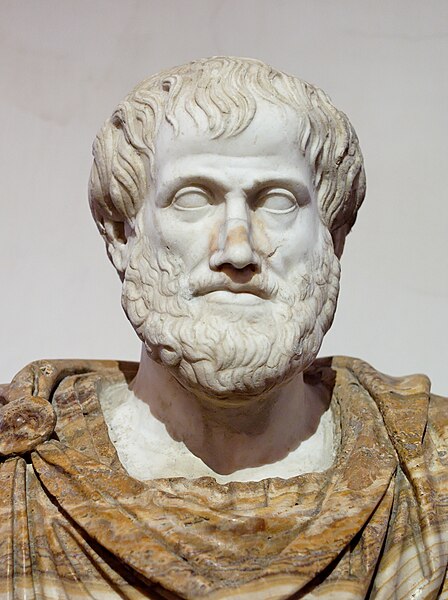

Aristotle

discussed adaptation by natural selection long before Darwin, yet despite his fame this theory

remained ignored throughout antiquity. (Wikicommons)

Gabriel

Andrade and Maria Campo Redondo have come out with a paper on the ancient

Greeks and how they saw differences between human groups:

Critics

of Rushton and Jensen, and of the very category of race, claim that race is a

social construct that only came up in the 16th century, as a result of overseas

voyages and the Atlantic slave trade. The goal of this article is to refute

that particular claim, by documenting how, long before the 16th century, in

classical antiquity race was already a meaningful concept, and how some Greek

authors even developed ideas that bear some resemblance to Rushton and Jensen's

theory. The article documents how ancient Egyptians already had keen awareness

of race differences amongst various populations. Likewise, the article

documents passages from the Hippocratic and Aristotelian corpus, which attests

that already in antiquity, there was a conception that climatic differences had

an influence on intelligence, and that these differences eventually become

enshrined in fixed biological traits. (Andrade and Redondo 2019)

The

ancients knew about psychological differences between human groups but usually put

them down to the direct action of the climate. This environmental explanation

seemed disproved by black Africans, or "Ethiopians" as they were

called, because they and their descendants remained just as dark-skinned at

northern latitudes. But this example of heritability didn't lead to a theory of

genetics. Instead, black skin was seen as an indelible stain, perhaps due to

divine punishment of Ham (or Cham), the ancestor of the Egyptians and black

Africans, for seeing the nakedness of his father Noah (Goldenberg 2003). This

view appears in a homily by the third-century Christian writer Origen:

But

Pharao easily reduced the Egyptian people to bondage to himself, nor is it

written that he did this by force. For the Egyptians are prone to a degenerate

life and quickly sink to every slavery of the vices. Look at the origin of the

race and you will discover that their father Cham, who had laughed at his

father's nakedness, deserved a judgment of this kind, that his son Chanaan

should be a servant to his brothers, in which case the condition of bondage

would prove the wickedness of his conduct. Not without merit, therefore, does

the discolored posterity imitate the ignobility of the race. Homily on Genesis

XVI

(Origen 2010)

In

general, human differences were attributed to direct action by the environment:

Greek

authors to a large extent believed that acquired characteristics were

inherited. For example, the text On Airs,

Waters and Places considers the people of Trapezus, who had the custom of

artificially elongating their children's heads. The author of this text

believed that this particular practice would make elongated heads in the future

generations, without parents having to artificially do the procedure: "Thus,

at first, usage operated, so that this constitution was the result of force:

but, in the course of time, it was formed naturally; so that usage had nothing

to do with it... If, then, children with bald heads are born to parents with

bald heads; and children with blue eyes to parents who have blue eyes; and if

the children of parents having distorted eyes squint also for the most part;

and if the same may be said of other forms of the body, what is to prevent it

from happening that a child with a long head should be produced by a parent

having a long head?". Aristotle had similar ideas: "Mutilated young

are born of mutilated parents".

Why wasn’t natural

selection understood?

Ironically,

and long before Darwin, the Greek philosopher Empedocles (494-434 BC) came up with another explanation: adaptation

through natural selection. Change initially occurs by accident. If the change

is good, the changed life-form will survive and reproduce; if not, it will

perish. Good changes are therefore kept and bad changes lost. Thus, all aspects

of living matter look "as if they were made for the sake of

something," but this is only illusion. There is no conscious

"maker" of all things.

This idea was summarized by Aristotle (384-322 BC):

So

what hinders the different parts (of the body) from having this merely

accidental relation in nature? as the teeth, for example, grow by necessity,

the front ones sharp, adapted for dividing, and the grinders flat, and

serviceable for masticating the food; since they were not made for the sake of

this, but it was the result of accident. And in like manner as to other parts

in which there appears to exist an adaptation to an end. Wheresoever,

therefore, all things together (that is all the parts of one whole) happened

like as if they were made for the sake of something, these were preserved,

having been appropriately constituted by an internal spontaneity; and

whatsoever things were not thus constituted, perished and still perish. Physicae

Auscultationes

2:8, 2 (Darwin 1936 [1888], p. 3)

Aristotle's fame, as well as Empedocles', ensured that this idea would be read and passed on for generations, and

yet it failed to take root in the minds of

classical antiquity. It fell on barren ground. Aristotle himself rejected it, saying that all things must be for an end. Only much later, and

independently, would natural selection be rediscovered.

The

difficulty was not in understanding that humans, like other animals, are

adapted to their environment. That part was obvious. The difficulty was in understanding

adaptation as an indirect process. People more easily understood direct processes:

something changed some people, and that change was passed on to their

descendants. Aristotle himself fell for that idea when he mused that mutilated

young are born to mutilated parents.

This

was the mentality of classical antiquity, and indeed of many people today.

Change implies the existence of a changer, just as creation implies the

existence of a creator. Few people rose above that level of thinking.

Did most people in

classical antiquity think like children?

A

Swiss psychologist, Jean Piaget (1896-1980), studied children in his country

and concluded that all individuals go through stages of mental development.

Children go through a "pre-operational stage" when causality is

understood only in terms of conscious intent, specifically animism,

artificialism, and transductive reasoning:

Animism

is the belief that inanimate objects are capable of actions and have lifelike

qualities. An example could be a child believing that the sidewalk was mad and

made them fall down, or that the stars twinkle in the sky because they are

happy. Artificialism refers to the belief that environmental characteristics

can be attributed to human actions or interventions. For example, a child might

say that it is windy outside because someone is blowing very hard, or the

clouds are white because someone painted them that color. Finally, precausal

thinking is categorized by transductive reasoning. Transductive reasoning is

when a child fails to understand the true relationships between cause and

effect. Unlike deductive or inductive reasoning (general to specific, or

specific to general), transductive reasoning refers to when a child reasons

from specific to specific, drawing a relationship between two separate events

that are otherwise unrelated. For example, if a child hears the dog bark and

then a balloon popped, the child would conclude that because the dog barked,

the balloon popped. (Wikipedia 2019)

Piaget

correctly observed Swiss children in the mid-20th century. He incorrectly

concluded that the mind develops at the same pace in all humans (Oesterdiekhoff

2012). Indeed, you need not go far back to reach a time when most individuals

never developed beyond the pre-operational stage. Just go back to classical

antiquity.

At

that time, the smart fraction was relatively small. Most intellectuals seemed

to be loners. There were no academic societies, no academic journals, and no

indications that large numbers of scholars did, or could, interact with each

other. This point is made in an article on Roman science:

According

to Sarton, who is the foremost living historian of science, "Roman science

at its best was but a pale imitation of the Greek." "The

Romans," he continues, "were so afraid of disinterested research that

they discouraged any investigation the utilitarian value of which was not

obvious."

Reymond

remarked in his "History of Science" that the Romans were never

distinguished for any love or even interest in pure science or abstract

thinking. Virtually the same conclusion was reached by Heiberg, and Fowler made

the interesting observation that even their literature and their philosophy had

a practical object.

[...]

historians of the economic life of ancient Rome have shown that there was a

surprising paucity of inventions. They were not only few in number, but they

lacked originality and were unimportant. (Salant 1938)

The

Roman Empire was organizationally strong but intellectually weak. It depended

on a store of knowledge that had been laid up in earlier times, notably by the

ancient Greeks. This was the prevailing opinion among Roman writers, an opinion

today dismissed as nostalgia for a mythical golden age.

The evidence of

ancient DNA

"Cognitive

archaeology" is a new field that has been made possible by retrieval of

DNA from human remains and by calculation of polygenic cognitive scores from

this DNA (based on alleles associated with educational attainment).

To

date, two studies have used these research tools to chart changes in mean

intelligence. The first study used ancient DNA from Europe and central Asia and

found that the polygenic cognitive score gradually increased between 4,560 and

1,210 years ago (Woodley of Menie et al 2017).

This

finding has been nuanced by a second study, using a sample of ancient DNA that

was much larger and only from ancient Greece. It found that mean intelligence

was initially high in ancient Greece and then began to decline after the end of

the Mycenaean period in 1100 BC (Woodley of Menie et al. 2019). It looks like

intelligence was at first strongly advantageous as humans adapted to increasing

social complexity: farming, sedentism, literacy … Then something made it much

less advantageous.

Mean

intelligence was therefore lower during Roman times in comparison both to Greece

in earlier periods and to Europe in later periods.

Conclusion

So

was Aristotle the Gregor Mendel of natural selection? Not really. Aristotle was

much more famous than Mendel, and his works were read over a much longer span

of time. Furthermore, Mendel's findings had to wait only 35 years before

getting their due recognition. Aristotle's thoughts on natural selection lay

dormant for more than two millennia before their significance was pointed out

to Charles Darwin.

Aristotle

didn't suffer from being insufficiently known. He had a worse handicap,

especially in this case: not enough people could understand his line of reasoning.

He was a lone voice in the wilderness over the many centuries separating him

from Darwin. By Darwin’s time, many more people could understand natural

selection, both in absolute numbers and as a proportion of the population. Even

before The Origin of Species Darwin

had a large audience of thinking people who could answer his questions and

comment on his ideas. Earlier thinkers were not so lucky.

In

the final analysis, the people of classical antiquity failed to understand

natural selection for the same reason they failed to understand economics. They

preferred to imagine cause and effect in simple terms: a person or personified thing

producing a big change over a short time, and not impersonal forces producing

an accumulation of small changes over a long time. They thought like children.

References

Andrade,

G. and M.C. Redondo. 2019. Rushton and Jensen's Work Has Parallels with Some

Concepts of Race Awareness in Ancient Greece. Psych 1 (1): 391-402.

https://www.mdpi.com/2624-8611/1/1/28/htm

Aristotle. Physics

http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/physics.2.ii.html

Darwin,

C. (1936) [1888]. The Origin of Species

and The Descent of Man. reprint of 2nd ed., The Modern Library, New York:

Random House.

Goldenberg,

D.M. (2003). The Curse of Ham. Race and

Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton: Princeton

University Press.

Oesterdiekhoff,

G.W. (2012). Was pre-modern man a child? The quintessence of the psychometric

and developmental approaches. Intelligence 40: 470-478.

http://www.iapsych.com/iqmr/fe/LinkedDocuments/oesterdiekhoff2012.pdf

Origen (2010). Homilies on Genesis and Exodus, transl. by R.E.

Heine., Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press

https://books.google.ca/books?id=X_mSBavPcq4C&pg=PA214&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false

Salant,

W. (1938). Science and Society in Ancient Rome. The Scientific Monthly 47(6): 525-535.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/16625?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Woodley,

M.A., S. Younuskunju, B. Balan, and D. Piffer. (2017). Holocene selection for

variants associated with general cognitive ability: comparing ancient and

modern genomes. Twin Res Hum Genet

20: 271-280.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/twin-research-and-human-genetics/article/holocene-selection-for-variants-associated-with-general-cognitive-ability-comparing-ancient-and-modern-genomes/BF2A35F0D4F565757875287E59A1F534

Woodley

of Menie, M.A., J. Delhez, M. Peñaherrera-Aguirre, and E.O.W. Kirkegaard.

(2019). Cognitive archeogenetics of ancient and modern Greeks. London Conference on Intelligence

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UES_tpDxz9A

Wikipedia

(2019). Piaget's theory of cognitive

development. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piaget%27s_theory_of_cognitive_development#Concrete_operational_stage

.jpg/450px-%E3%83%AD%E3%83%9D%E3%83%83%E3%83%88%E7%84%A1%E4%BA%BA%E3%82%B3%E3%83%B3%E3%83%93%E3%83%8B_ROBOT_MART_(44883311244).jpg)