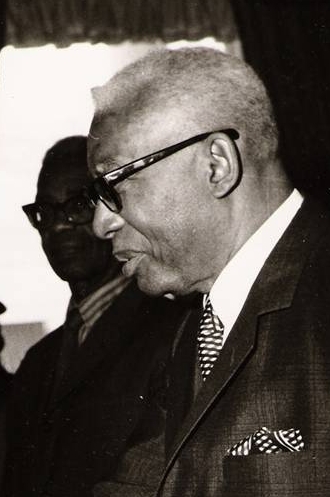

François Duvalier, President

of Haiti (1957-1971)

In 1957, François Duvalier was

elected President of Haiti. He won massively: 679,884 votes to the 266,992 of

his nearest frontrunner, Louis Déjoie. Once in power he exiled Déjoie's major

supporters and had a new constitution proclaimed. He then seized control of the

army and created a militia, the Tonton

Macoutes, that became twice as big as the army. In 1961, he called a new

presidential election and ran as the sole candidate. In 1964, he became

president for life. In 1966, he persuaded the Vatican to allow him to nominate

the country's Catholic hierarchy. "No longer was Haiti under the grip of

the minority rich mulattoes, protected by the military and supported by the

church; Duvalier now exercised more power in Haiti than ever." (Wikipedia

2018).

He is still well known almost

a half-century after his death:

Duvalier's government was one of the most repressive in the hemisphere. Within the country he murdered and exiled his opponents; estimates of those killed are as high as 60,000.

Duvalier employed intimidation, repression, and patronage to supplant the old mulatto elites with a new elite of his own making. Corruption—in the form of government rake-offs of industries, bribery, extortion of domestic businesses, and stolen government funds—enriched the dictator's closest supporters. Most of them held sufficient power to intimidate the members of the old elite, who were gradually co-opted or eliminated.

Many educated professionals fled Haiti for New York City, Miami, Montreal, Paris and several French-speaking African countries, exacerbating an already serious lack of doctors and teachers.

The government confiscated peasant landholdings and allotted them to members of the militia, who had no official salary and made their living through crime and extortion. The dispossessed fled to the slums of the capital where they would find only meager incomes to feed themselves. Malnutrition and famine became endemic. (Wikipedia 2018).

The noiriste revolution of

1946

This political revolution did

not begin in 1957. Duvalier himself said he was continuing what had begun in

1946 with the election of Dumarsais Estimé, the first black president after

more than two decades of American occupation and another two decades of

authoritarian mulatto rule. Duvalier had in fact served under Estimé, first as

Director General of the National Public Health Service and then in 1949 as

Minister of Health and Labor.

By firing mulatto civil

servants, and by greatly expanding the civil service, Estimé greatly expanded Haiti's

black middle class, and it was especially this group that would provide

Duvalier with his core support. Duvalier wanted to reduce mulatto

overrepresentation even further, not only in the public sector but also in the

private sector. He succeeded, but only made life worse for most Haitians. When

the anthropologist Micheline Labelle went to Haiti in the 1970s, she found

widespread disappointment among her interviewees:

"Currently, the greatest personal fortunes could be among the blacks (Duvalier, Cambronne ...). There are very rich blacks in the bureaucratic middle class but it amounts to 20, 30 senior officials only. For the others, nothing has changed" (middle-class mulatto man, 25 years old). (Labelle 1987, p. 192)

Duvalier did reduce mulatto control of the economy, but at the cost of cultural changes that made wealth creation much harder. Less mulatto wealth did not create more for the black middle class, let alone for blacks in general. These cultural changes are mentioned in Labelle's interviews and involved several areas of behavior.

Trust

Haiti is a low-trust culture.

Labelle gives the example of a fire at the Tippenhauer plant in 1973:

As in other assembly plants where workers are searched at the exit for fear of theft, all of the emergency exits had been locked to ensure control. A fire broke out and caused around twenty deaths. (Labelle 1987, p. 203)

Mulatto interviewees were wary

of blacks from all walks of life:

[...] domestics especially, who become for the [mulatto] women a sort of major referent, an obsessive preoccupation, due to fear of coulage (theft), poisoning, magic; [the interviewees] fear that workers in plants will steal [...]; [they] fear that poor street people will plunder or even murder [...]; [they] fear that the [black] "middle classes" in power will bring objective repression: torture, murders, disappearances, exile [...] (Labelle 1987, pp. 203-204)

Blacks were reportedly no less mistrustful:

[According to middle-class mulattoes] a negro is mistrustful because he is afraid. This is a peasant trait. Blacks have no principles, no education. So they have to fight to keep going. The black man has been traumatized since childhood. He saw his parents bail out [se dégager]. So he will do the same.

Blacks of both sexes spoke about their mistrust of each other:

In this way, the idea of betrayal invades relationships between men and women. Many women are convinced that any man will cheat on any woman morally, physically, and intellectually. Many men, being convinced that behind each woman hides a slut [bouzin], may, by a sort of compensatory response, become compulsive experts in the art of bringing down [faire chuter] a woman previously considered decent [honnête]. (Labelle 1987, p. 229)

"People scorn women here. One doesn't confide in a woman. When you come down to it, she's a whore, ready to do anything for money [...]. We talk about this between men. We laugh about it, and it's deeply anchored. Men, frankly, are buddies with each other [complices]. This is due to the situation of women during slavery. They managed better than men thanks to their sexual attributes. This attitude has perpetuated itself among them. They calculate [...]” (middle-class black man, 45 years old). (Labelle 1987, p. 229)

Thus, the middle-class black man, like the man of other social classes, is literally torn between the ideal of a faithful wife and his scorn for a woman, whatever her color: Koko pa gin zorèy, mè l'tandé brui lajan [A vagina has no ears, but it hears the sound of money] (Labelle 1987, p. 229)

[...] the idea that one cannot trust women, independently of their color, remains implicit. The fear of being tricked, poisoned, betrayed by a woman is profound in the peasant milieu. (Labelle 1987, p. 265)

A Haitian man, people say again and again, cannot conceive that he must limit himself to one woman at a time. Women are socialized in this axiom since childhood; they expect men to behave freely and are resigned to this. On the other hand, men cannot conceive that their wives will be unfaithful and are perpetually obsessed by the fear of being cheated on. (Labelle 1987, p. 228)

Honesty

As noted in my last post, most

of the middle-class mulattoes refrained from commenting on this subject. Those

who did felt that the black middle class was less honest than the mulatto

middle class, while taking care to qualify this judgment:

"If I have to employ someone as an accountant, cashier, or domestic, and if I don't know any of them, I'll choose a mulatto because they have a reputation of being educated and honest, but if I have records and if I see recommendations, I'll choose just as much a black" (middle-class mulatto, 36 years old). (Labelle 1987, p. 202).

"There's no better thief than #1 [a figure representing a black man], that's understandable, they're in poverty... In fact I can't categorize. It's a matter of individuals, not of types. Except for the regime. [there] it's widespread. Everybody has the right to a cut...And with Duvalier's police, it's even worse. They've been taking their cut from the top to the bottom, throughout the country" (middle-class mulatto man, 25 years old). (Labelle 1987, p. 202).

This kind of observation was also made by many of the middle-class blacks:

"[You] talk about honesty these days in Haiti! You make me laugh. [...] One sees so many things these days. You think so-and-so is honest and you discover he does tons of dirty things [...]. A griffe [three-quarters black, one quarter white] perhaps would be more honest [...]. But in any case not a black man because he'll seek by any means to get in with the mulattoes and crush the others. What's disappointing is that when they get into power, they plunder. All of them do the same thing” (middle-class black woman, 22 years old). (Labelle 1987, p. 208)

Goodwill

According to Labelle, the

Duvalier era brought an increase in jealousy to middle-class society. "Mulatto women are

considered to be generally more frank, resorting less to magic practices

against each other, spreading fewer rumors, and being less envious than black

women" (Labelle 1987, p. 209). Jealousy became not only more common but

also more ruthless:

“Women are fighting among themselves. Jealousy all the time. They seek by any means to hurt you. In the past, it wasn't so hard. These days it's a really big thing. Before there used to be a mulatto elite who had nothing to do with these superstitious things. But black women want to get ahead. They seek by any means to nail you [régler] for things to do with husbands or homes. It's a constant struggle. If you have a conspicuous social condition, you'll be envied, you'll be sent an illness to make you spend money. Someone will find something near a gate [to the house...]. Spirits will be sent to disrupt that house[hold...]. Your child at school will be made fun of [...]” (black middle-class woman, 42 years old). (Labelle 1987, p. 209)

Future time orientation, teamwork, self-control, etc.

This area of behavior was

covered in my last post. Both mulatto and black interviewees said that the

mulatto man knows how "to make money work." He is business-minded and

knows how to team up with others. In contrast, the middle-class black man

"accumulates to show off, refuses to invest, spends outrageously, and does

not know how to administer his assets." (Labelle 1987 pp. 191-196). In short, mulattoes adhere to middle-class values. "Mulattoes, it

is said, have more cohesion, solidarity, respect for their word when given,

self-control, sense of responsibility, and scruples. The black man is cunning,

mistrustful, thieving, untruthful, treacherous, politically irresponsible, and

corrupt" (Labelle 1987, p. 198).

Conclusion

Until the American occupation,

Haiti had two parallel societies. On the one hand, the mulatto community held European middle-class values and provided the country with lawyers, doctors,

businessmen, merchants, politicians, and civil servants. On the other hand, the

black community lived as small farmers with perhaps 10% living in town as artisans, mill and factory workers, petty

traders, or government officials of one sort or another. Farmers typically

grew enough food to meet their own needs plus a small surplus for the

marketplace. Trade was women's work:

The peasant's creativity is perhaps furthered by the widespread custom of polygamy, since each wife acts as the business manager of her household, thus freeing her husband for more spiritual tasks.

[...] The woman is the organizer. She cooks, washes, rears the children, handles the finances, and makes all purchases, excepting the animals. She lugs the produce to the nearest market or sells it to a middleman speculator who in turn peddles it in the city. On market day she can be seen striding along the jungle paths to market, balancing a basket of produce on her head as regally as a queen with an outsize crown. (Diederich and Burt 1969, pp. 21-22)

Business acumen was thus limited to women, and even they lacked some key elements, particularly the willingness to work as a team with non-kin on a common project. For both the private and public sectors, administrative and organizational skills were confined to the mulatto community.

Things began to change with

the American occupation. For the first time in Haiti's history large numbers of

blacks received postsecondary education and entered the civil service (Kaussen

2005, p. 69). The new American style of education was democratic—it aimed to

teach large numbers of people the vocational skills needed for specific jobs.

This was in contrast to the old model of providing a small elite with administrative

and organizational skills—teaching rulers how to rule, with strong emphasis on

law, the humanities, and classical studies:

The Haitian elite followed the aristocratic prejudice of honoring literary and professional work and despising manual labor. Hard physical work was linked in their minds with slavery and regarded as the prerogative of the ignorant and the poor. They feared that American influence might direct their educational system away from French cultural traditions and toward more materialistic goals. (Diederich and Burt 1969, pp. 35).

Duvalier was a product of both systems. He had gone to an old-style lycée for primary and secondary education but then attended an American-reorganized medical school and was later hired for a U.S. army project to control yaws, an infection of the skin, bones, and joints (Diederich and Burt 1969, pp. 36, 48-49).

In 1946, Dumarsais Estimé

became Haiti's first democratically elected black president. He sought to

expand opportunities for his country's emerging black middle class; first by

replacing mulattoes with blacks in the civil service, and second by greatly

expanding the civil service. This new middle class would increasingly be at

odds with its older mulatto counterpart:

The blacks concentrated on politics but failed to expand their power by developing outside business connections. They simply enriched themselves in an opportunistic fashion by their mismanagement of public funds during a favorable economic period, emerging as a sort of "black elite," thus challenging the mulatto establishment which had a broader base of power.

[…] The behavior of the new black elite, now in privileged positions, caused problems. Their lack of discipline, and often mere greed, began to have repercussions. There was a political-business scandal in the banana industry. Also, some prominent black officials were charged with graft in the construction of the exposition. The rift between black and mulatto widened. (Diederich and Burt 1969, pp. 56-57)

In theory, Haiti should have benefited by making its educational system more democratic, more vocational, and more merit-based. Unfortunately, learning how to work is more than simply learning how to perform a task. A task is performed in a social context where you work with people who are not necessarily your family or kin, where you resolve disputes without violence, where your property rights are respected and theft stigmatized, and where you look beyond the task at hand and assess its long-term consequences. These lessons are not taught at a vocational school. After the American occupation ended, President Sténio Vincent (1930-1941) recognized this shortcoming and sought to remedy it through national Catholic education for the masses, such as Mussolini had introduced in Italy, Franco in Spain, and Pétain in Vichy France. Whether such a social model would have succeeded in Haiti is debatable. In any case, it was no longer realistic by 1941, when the U.S. was preparing for war against the Axis, and when Roosevelt pressured Vincent to step down.

A tragedy is the inevitable

working out of a mistake and its consequences. The 1946 election, and the rise

of noirisme, put Haiti on a path that

led to Duvalier. Even if he had been deposed, as had almost happened on several

occasions, someone like him would have taken his place. The problem was his

power base—a black middle class that envied its mulatto counterpart and blamed

its failings on everything and everyone, except itself.

Today, Haiti is a broken

nation that has destroyed much of its social capital. This destruction will be especially

hard to undo because too many Haitians still disown responsibility for what has

happened to their country. One instead hears a litany of excuses: the

Napoleonic invasion in 1802, the refusal of the U.S. to recognize Haiti, and

the massive reparations to France. Yet the French were finally ousted in 1804,

the United States recognized Haiti in 1862, and the final payment to France was

made in 1947. In that year, Haiti’s future seemed promising ...

References

Diederich, B. and A. Burt.

1969. Papa Doc. The Truth about Haiti

Today, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kaussen, V. (2005). Race,

Nation, and the Symbolics of Servitude in Haitian Noirisme, in A.

Isfahani-Hammond (ed.). The Masters and

the Slaves. Plantation Relations and Mestizaje in American Imaginaries (pp.

67-88), New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

https://books.google.ca/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=tX7HAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA67&ots=9n5kLms9lz&sig=2qI-YwbmPd9SjlH942Pqo71HbE8#v=onepage&q&f=false

Labelle, M. (1987). Idéologie de couleur et classes sociales en

Haïti, Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal.

http://classiques.uqac.ca/contemporains/labelle_micheline/ideologie_de_couleur_en_haiti/labelle_ideologie_couleur.pdf

Wikipedia (2018). François

Duvalier

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/François_Duvalier

4 comments:

How many college graduates in Haiti?

Why is Haiti tragic? The social patterns you describe are found in every black community from Africa to the Caribbean to the Brazilian and American black ghettos. These patterns are not choices. They are the result of black evolution in Africa, and they are genetically based, written in black DNA. Consequently, the results you view as tragic are simple the working out of the black genes.

Mulattos differ from true blacks because of their white ancestry. Whites evolved in a radically different environment than Africa, their ancient home, and white social patterns are also written in their DNA. It is unfortunate that due to illness hbd chick no longer posts (but the page is still there for viewing) because she extended the genetic analysis to differences in European populations.

Part of the problem in the US is that ghetto blacks are expected to behave like suburban middle class whites, despite the differences in evolutionary history.

Peter, isn't this a case of a tiny but politically and economically ethnic minority being dislodged by the majority. Amy Chau points out in her latest book that the South Vietnamese saw the communist war against “capitalists” as war against the ethnically Chinese elite in the south who were 1% of the population, but owned 80% of the economy and also constituted much of the command structure of the Viet Cong. Yet in the end they were expelled (Boat people). Haiti was tragic in the sense there was an inevitability about a black takeover.

sykes 1, US Blacks all used to live together in relatively orderly black areas, then the middle class blacks left for the suburbs, and that is when those areas became hell hole ghettos. Low class blacks were behaving differently before black communities were denuded of their middle class. Black countries are the same. Even in Africa, I expect things will deteriorate as the middle classes will progressively leave.

Luke,

"less than 1% of Haiti’s young people will go on to receive a university degree in Haiti."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Education_in_Haiti#Higher_education

Sykes,

A tragedy isn't simply a story that ends badly. It's a story that ends badly because certain choices lead inevitably to a bad ending. Typically, these choices seemed good at the time. During the American occupation, a decision was made to expand opportunities for vocational training. This created a new black middle class who were much better off than the majority of Haitians, but who preferred to compare themselves with the existing mulatto middle class. The result was a climate of jealousy that brought black nationalist governments to power: first with Estimé in 1946 and then with Duvalier in 1957. Mulattos were progressively excluded from the public sector and then from much of the private sector. Many left the country and others were killed by the Tonton Macoutes, see Jérémie Vespers http://dictionary.sensagent.com/jeremie%20vespers/en-en/

I don't wish to downplay genetic influences, but there is an interaction between genetics and culture. At the time of the Moynihan Report (1965), the illegitimacy rate was 25% in the African American community. Now, it's 75%. There has been a destructuring of social life in the black community over the past half-century as a result of the declining influence of the church, the loss of stable unionized employment, and the dispersal of the black middle class into the larger white community. The first two trends are not limited to African Americans, but they have had a much greater impact on them, probably because African Americans do not perform well in an atomized, individualistic environment. Before 1965, black communities were better structured, with stronger families, stronger churches, and greater presence and leadership by the black middle class.

Sean,

Not by the majority. By the new black middle class that arose in the 1930s and 1940s. The majority of Black Haitians didn't benefit at all under Duvalier's regime. You're right though, in the sense that comparisons can be drawn with other Third World countries that gained independence after the war. Power was often seized by a new elite that was more intent on plundering either what remained of the colonial administration or the local middleman minorities (South Asians in East Africa and Guyana, Chinese in South-East Asia, Greeks and other Christians in the Middle East, etc.

Post a Comment