One

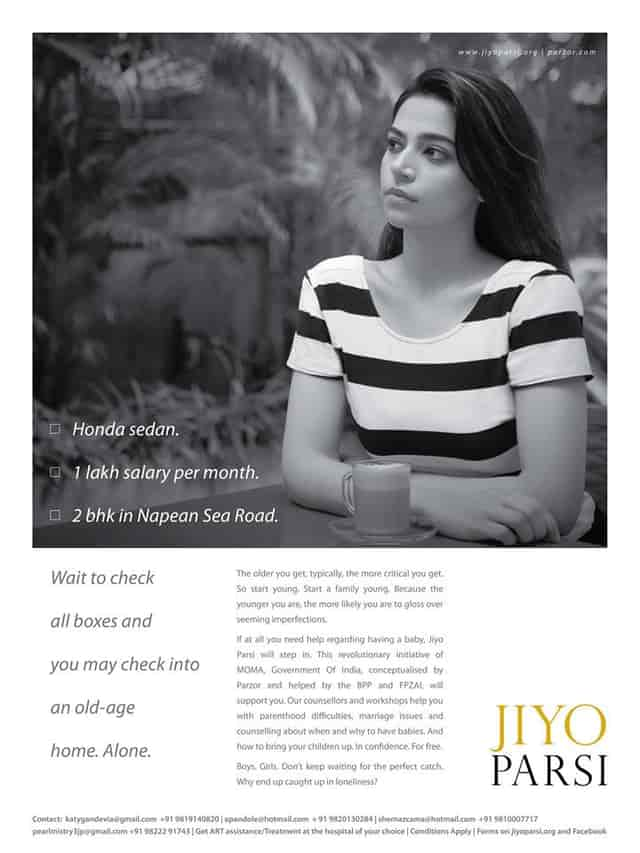

of several posters to promote family formation in the dwindling Parsi community

(Jiyo Parsi)

In

India, and overseas, the Parsis are renowned for their achievements,

particularly in business but also in science, culture, and philanthropy.

They are also known for something else: they’re dying out. From 114,000 in 1941, they were down to half that number by 2011. Today, more than 30% of Parsis don't marry, and an equal proportion are over 60 years old. Their fertility rate is 0.8—in other words, the average Parsi woman gives birth to less than one child during her lifetime. This existential crisis is worrying not only the Parsis but also the Indian government. In 2013, a program was set up to subsidize fertility treatments and promote family formation in the community (Dore 2017).

They are also known for something else: they’re dying out. From 114,000 in 1941, they were down to half that number by 2011. Today, more than 30% of Parsis don't marry, and an equal proportion are over 60 years old. Their fertility rate is 0.8—in other words, the average Parsi woman gives birth to less than one child during her lifetime. This existential crisis is worrying not only the Parsis but also the Indian government. In 2013, a program was set up to subsidize fertility treatments and promote family formation in the community (Dore 2017).

Extinction

is irreversible. If the Parsis die out, the loss will be greatest in those

things we don’t fully understand: the workings of the human mind. That is

precisely where the Parsis have succeeded the most. How much of that success

has been due to learning and how much to innate factors?

A

few steps toward an answer were taken by Greg Cochran and Henry Harpending in

their paper on Ashkenazi intelligence:

Since strong selection for IQ seems to be unusual in humans (few populations have had most members performing high-complexity jobs) and since near-total reproductive isolation is also unusual, the Ashkenazim may be the only extant human population with polymorphic frequencies of IQ-boosting disease mutations, although another place to look for a similar phenomenon is in India. In particular, the Parsi are an endogamous group with high levels of economic achievement, a history of long-distance trading, business and management, and who suffer high prevalences of Parkinson disease, breast cancer and tremor disorders, diseases not present in their neighbours. (Cochran et al. 2006)

Such

disorders may be a side-effect of strong selection for intelligence over a

short time in a small population. This was historically the case with Ashkenazi

Jews. They are unusually prone to four neurological disorders: Tay-Sachs,

Gaucher, Niemann-Pick, and mucolipidosis type IV. All four affect the brain by

increasing the capacity of lysosomes to store sphingolipid compounds for axonal

growth and branching. Furthermore, Tay-Sachs is caused in Ashkenazi Jews by two

unrelated mutations and Gaucher disease by five. Random chance simply cannot

explain why so many mutations exist in the same metabolic pathway and have reached

such high frequencies.

Those

mutations apparently spread through heterozygote advantage. Though harmful when

two copies are inherited from both parents, they are beneficial when only one

copy is inherited, as is more often the case. With a better supply of sphingolipids

and no adverse effects, the brain can process information more efficiently.

Jared

Diamond (1994) was the first to argue that chance cannot explain the high

prevalence of so many lysosome storage disorders in a single population. He suggested

the cause was selection for intelligence. His theory was then developed by

Cochran et al. (2006). Other researchers have further confirmed Diamond’s

theory by showing that Ashkenazim have high frequencies of alleles associated

with educational attainment (Dunkel et al. 2019; Piffer 2019).

Frequent

neurological/cerebral diseases among the Parsis

We

see a similarly high prevalence of neurological or cerebral diseases among the

Parsis. Parkinson’s disease is considerably more prevalent among them than

among other Indians or even people of developed countries. Strokes are at least

twice as common. Essential tremors are exceptionally frequent (Gourie-Devi

2014).

These

diseases seem to have a genetic basis among the Parsis. A mitochondrial genome

study found 420 unique genetic variants within that community, 178 of which are

associated with Parkinson's disease. Others are linked to other

neurodegenerative disorders, as well as colon, breast, and prostate cancer. A

surprising number of these unique variants, 217, are linked to increased longevity.

Finally, and perhaps curiously, some variants are linked to asthenozoospermia,

i.e., reduced sperm motility (Patell 2020)

The

above results are consistent with the findings of an earlier genetic study of

the Parsis, specifically their autosomal, Y chromosome, and mitochondrial DNA.

Signals of selection were strongest in SNPs associated with humoral immunity,

cerebellar physiology, and neurological disorders like early epilepsy (Lopez et

al. 2017).

Conclusion

The

evidence is only suggestive, but it looks like the Parsis have undergone strong

selection for intelligence over a relatively short time; hence, the high

prevalence of neurological disorders.

In

addition, this community seems to have adapted to its economic and social niche

through a "slow life history" strategy. The Parsis are predisposed to

live longer and thus learn more over a longer time. They may also be

predisposed to longer birth intervals and higher parental investment in each

child (K selection). Such a reproductive strategy is consistent with lower male

fertility.

A

slower life history, combined with higher intelligence, may have assisted the trading

lifestyle of the Parsi community. Trade requires a high level of cognitive

ability, particularly for literacy and numeracy, as well as lower time

preference and a longer learning period.

Ironically,

low time preference may explain the demographic decline of the Parsis, and

other people like them. If you’re future-oriented, you’re also keenly aware of

future costs, particularly those of getting married and having a family. So you’ll

postpone marriage and family formation until you’re financially ready.

Unfortunately, that day may never come. Or it may come too late.

This

problem was known to traditional societies, and there used to be social

incentives to ensure that young people would marry before they got too old. Unfortunately,

those incentives have disappeared in modern societies.

If you wait to

check all the boxes, you may check into an old-age home … alone.

References

Cochran,

G., J. Hardy, and H. Harpending. (2006). Natural history of Ashkenazi

intelligence. Journal of Biosocial

Science 38: 659-693

Diamond,

J.M. (1994). Jewish Lysosomes. Nature

368: 291-292.

Dore,

B. (2017). Glimmer of hope at last for India's vanishing Parsis. BBC News

Dunkel,

C.S., Woodley of Menie, M.A., Pallesen, J., and Kirkegaard, E.O.W. (2019).

Polygenic scores mediate the Jewish phenotypic advantage in educational

attainment and cognitive ability compared with Catholics and Lutherans. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences 13(4):

366-375.

Gourie-Devi

M. (2014). Epidemiology of neurological disorders in India: review of

background, prevalence and incidence of epilepsy, stroke, Parkinson's disease

and tremors. Neurology India 62(6):

588-598. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.149365

López,

S., Thomas, M. G., van Dorp, L., Ansari-Pour, N., Stewart, S., Jones, A. L.,

Jelinek, E., Chikhi, L., Parfitt, T., Bradman, N., Weale, M. E., and Hellenthal,

G. (2017). The genetic legacy of Zoroastrianism in Iran and India: insights

into population structure, gene flow, and selection. American Journal of Human Genetics 101(3): 353-368.

Patell,

V.M., N. Pasha, K. Krishnasamy, B. Mittal, C. Gopalakrishnan, R.

Mugasimangalam, N. Sharma, A-K. Gupta, P. Bhote-Patell, S. Rao, R. Jain, and

The Avestagenome Project. (2020). The First complete Zoroastrian-Parsi

Mitochondria Reference Genome: Implications of 2 mitochondrial signatures in an

endogamous, non-smoking population. bioRxiv

preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.05.124891

Piffer,

D. (2019). Evidence for Recent Polygenic Selection on Educational Attainment

and Intelligence Inferred from Gwas Hits: A Replication of Previous Findings

Using Recent Data. Psych 1(1): 55-75.

7 comments:

You are always interesting.

So there are selection pressures against intelligence. Just like any other lifestyle there are costs and benefits.

It seems K isn't always adaptive

"Finally, and perhaps curiously, some variants are linked to asthenozoospermia, i.e., reduced sperm motility" Lacking lead in their pencil was not a tremendous disadvantage. But Pasi women seem, to me at least, to be a lot better looking than the men. I'll boldly speculate that selection for IQ* led to Parsi men with the cognitive ability to get rich and support huge families living in style, getting the most beautiful women as wives.

*Life Finds a Way, Andreas Wagner (2019) Page 14 "And during these experiments [Sewall] Wright noticed something odd: that selecting the best animals for reproduction--Fisher's formula for breeding success--when repeated over and over for multiple generations, did not always work well to create a superior breed. For example, during ongoing selection to create one trait like beef quality or mild yield, other traits also deteriorate, including two crucial ones: mortality and fertility"

Sean,

I don't know about Parsi women, but Persian women seem to invest a lot in their physical appearance.

"If you’re future-oriented, you’re also keenly aware of future costs"

Don't forget about risks. Having family, children etc. can lead to prison via the family court. This didn't happen in the remote past, eg. no one cared if some children died, so people could take risks.

It's not the Parsis but the small south Indian Brahmin community that have the highest IQ in India (Average IQ estimates of 120). They don't have all these diseases either.

The Parsis have these diseases because of a small founder population, exacerbated by extreme endogamy

Post a Comment