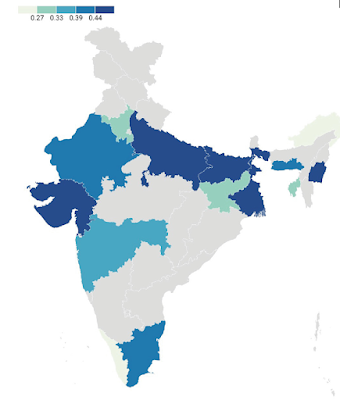

Geographic distribution of the G allele

(TIMPRSS2), which is associated with

a higher death rate from COVID-19. It’s most frequent on the Indo-Gangetic Plain,

which has the longest continuous history of urban settlement in South Asia. Did

that environment select for susceptibility to coronaviruses as a way to boost

resistance to deadlier respiratory viruses?

The

common cold is caused by over 200 strains of rhinoviruses, coronaviruses,

adenoviruses, and enteroviruses. Coronaviruses differ from other respiratory viruses

in one key respect: they can enter lung tissue via the ACE2 receptor. So if that receptor is altered to allow easier

entry, the host would become more susceptible to the common cold but not to

other respiratory diseases, including much deadlier ones that cause

tuberculosis, pneumonia, or pneumonic plague.

The

last point is important because there is evidence that a viral infection can

protect against subsequent infection by respiratory viruses. When mice are

infected with γherpesvirus 68, which is similar to Epstein-Barr virus, there is

production of large quantities of IFN-γ and activation of macrophages that

protect against Listeria monocytogenes

(which causes listeriosis), Mycobacterium

tuberculosis (which causes tuberculosis), and Yersinia pestis (which causes bubonic and pneumonic plague) (Barton

et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2019). A cytomegalovirus infection likewise

protects against Listeria monocytogenes

and Yersinia pestis (Barton et al.,

2007).

Coevolution

between coronaviruses and early urban settlement

Beginning

some 10,000 years ago, hunting and gathering gave way to farming, and nomadism

to sedentism. People began to live in progressively larger settlements along

the Nile in Egypt, the Tigris and the Euphrates in Mesopotamia, the Indus and

the Ganges in northern India, and the Yellow and the Yangtze in China. That is where

large numbers of humans first lived in close proximity to each other, and they

were particularly vulnerable to the spread of respiratory diseases from one

person to another. There may thus have been selection among them for increased

susceptibility to coronaviruses, which are normally mild in their effects, as a

means to increase resistance to deadlier respiratory viruses.

A

recent Indian study by Pandey et al. (2022) suggests that coronavirus

susceptibility may have coevolved with risk of infection by life-threatening

respiratory viruses like tuberculosis, pneumonia, and pneumonic plague, at

least in South Asia. People are more susceptible to infection by coronaviruses

if they have the G allele of the TMPRSS2

gene. The research team found that the G allele is significantly associated

with a higher fatality rate for COVID-19, apparently because it helps coronaviruses

enter lung tissue via the ACE2

receptor.

Pandey

et al. (2022) also charted the geographic distribution of the G allele in South

Asia. This allele is most frequent among inhabitants of the Indo-Gangetic Plain,

i.e., the fertile lowlands that border the Indus and Ganges rivers of northern

India and Pakistan. This is also where urbanization has existed for the longest

continuous time in South Asia, specifically since the early first millennium

BCE. The Indo-Gangetic Plain has had "an uninterrupted sequence of

economic development, state formation, and cultural expansion affecting the

entire subcontinent as well as Central, East and Southeast Asia" (Heitzman

2008, pp. 12-13).

These

findings are roughly consistent with an earlier finding by the same research

team. Srivastava et al. (2020) found that an ACE2 allele, at rs2258666, has a negative relationship with the

fatality rate for COVID-19. It is also most frequent in the northeast of India,

which until recent times was sparsely populated, and whose inhabitants lived in

dispersed rural settlements.

References

Barton,

E.S., D.W. White, J.S. Cathelyn, K.A. Brett-McClellan, M. Engle, et al. (2007).

Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature

447:

326-329.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05762

Frost,

P. (2020). Does a commensal relationship exist between coronaviruses and some

human populations? Journal of Molecular

Genetics 3(2): 1-2.

Heitzman,

J. (2008). The City in South Asia.

London: Routledge

Miller,

H.E., K.E. Johnson, V.L. Tarakanova, and R.T. Robinson. (2019). γ-herpesvirus

latency attenuates Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Tuberculosis 116: 56-60.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2019.04.022

Pandey,

R.K., A. Srivastava, P.P. Singh, and G. Chaubey. (2022). Genetic association of

TMPRSS2 rs2070788 polymorphism with COVID-19 case fatality rate among Indian

populations. Infection, Genetics and

Evolution 98 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2022.105206

Shirato,

K., M. Kawase, and S. Matsuyama. (2018). Wild-type human coronaviruses prefer

cell-surface TMPRSS2 to endosomal cathepsins for cell entry. Virology 517: 9-15.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2017.11.012

Srivastava,

A., A. Bandopadhyay, D. Das, R.K. Pandey, V. Singh, N. Khanam, N. Srivastava,

P.P. Singh, P.K. Dubey, A. Pathak, P. Gupta, N. Rai, G.N.N. Sultana, and G.

Chaubey. (2020). Genetic Association of ACE2 rs2285666 Polymorphism with

COVID-19 Spatial Distribution in India. Frontiers

in Genetics. September 25

https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.564741

5 comments:

Peter, now that COVID is ending (becoming endemic with Omicron), will the world go back to normal (i.e. the pre-2020 status quo), or has something changed? Was COVID a one-off event, or is it actually a sign of what could continue to cripple societies? Also, do you see any evidence that COVID could be "nature's response" to a world that's gotten too diverse and interconnected? While it existed, COVID gave the US the ability to reduce immigration, which would have otherwise been impossible in today's PC culture (deportations have become unacceptable). To the extent that it's ending, the future of America's "Title 42" allowing quick deportations of migrants at the border due to a health emergency could also be in question.

It's not a one-off event. There will be another global pandemic, and each successive pandemic is spreading more quickly and more globally than the previous one. The underlying problem is that (1) more people are travelling internationally and (2) border controls have become more relaxed. This increase in human mobility, together with the increasing size of the world's population, has created a tinderbox that pathogens will exploit within increasing ease.

Will the world react by closing up and separating? When Omicron escaped from South Africa, people bristled at the idea of restricting travel from there, even for a short period of time, which I found crazy. For some reason, the modern world is hysterically opposed to any kind of isolation or closed borders. They call it "insulting" or "unethical," and borders have become "racist." Will that attitude have to change?

Eventually, that attitude will have to change, but "eventually" might be a long time.

Few people change their minds overnight, especially if they have invested a lot of effort in promoting a particular mindset. There is one cause for hope: the elites have been disproportionately hurt by the pandemic because they tend to have a global, jet-setting lifestyle.

Very Insightful..Thank You for writing this wonderful blog on our research

Post a Comment