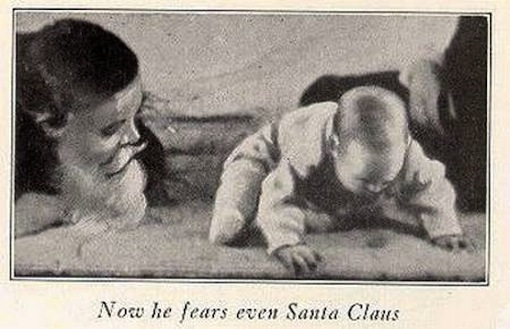

John

B. Watson conditioning a child to fear Santa Claus. With a properly controlled environment, he felt that children can be conditioned to think and behave in any way desired

After

peaking in the mid-19th century, antiracism fell into decline in the U.S.,

remaining dominant only in the Northeast. By the 1930s, however, it was clearly

reviving, largely through the efforts of the anthropologist Franz Boas and his

students.

But

a timid revival had already begun during the previous two decades. In the

political arena, the NAACP had been founded in 1910 under the aegis of WASP

and, later, Jewish benefactors. In academia, the 1920s saw a growing belief in

the plasticity of human nature, largely through the behaviorist school of

psychology.

The

founder of behaviorism was an unlikely antiracist. A white southerner who had

been twice arrested in high school for fighting with African American boys, John

B. Watson (1878-1958) initially held a balanced view on the relative importance

of nature vs. nature. His book Psychology

from the Standpoint of a Behaviorist (1919) contained two chapters on

"unlearned behavior". The first chapter is summarized as follows:

In

this chapter, we examine man as a reacting organism, and specifically some of

the reactions which belong to his hereditary equipment. Human action as a whole

can be divided into hereditary modes of response (emotional and instinctive),

and acquired modes of response (habit). Each of these two broad divisions is

capable of many subdivisions. It is obvious both from the standpoint of

common-sense and of laboratory experimentation that the hereditary and acquired

forms of activity begin to overlap early in life. Emotional reactions become

wholly separated from the stimuli that originally called them out (transfer),

and the instinctive positive reaction tendencies displayed by the child soon

become overlaid with the organized habits of the adult.

By

the mid-1920s, however, he had largely abandoned this balanced view and

embraced a much more radical environmentalism, as seen in Behaviorism (1924):

Our

conclusion, then, is that we have no real evidence of the inheritance of

traits. I would feel perfectly confident in the ultimately favorable outcome of

a healthy, well-formed baby born of a

long line of crooks, murderers and thieves, and prostitutes (Watson, 1924, p. 82)

[...]

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to

bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to

become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist,

merchant-chief, and yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents,

penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors. I am

going beyond my facts and I admit it, but so have the advocates of the contrary

and they have been doing it for many thousands of years. (Watson, 1924, p. 82)

Everything

we have been in the habit of calling "instinct" today is a result

largely of training—belongs to man's learned behavior. As a corollary from this

I wish to draw the conclusion that there is no such thing as an inheritance of

capacity, talent, temperament, mental constitution, and characteristics. These

things again depend on training that goes on mainly in the cradle. (Watson,1924, p. 74).

Why

the shift to extreme environmentalism? It was not a product of ongoing academic

research. In fact, Watson was no longer in academia, having lost his position

in 1920 at Johns Hopkins University after an affair with a graduate student. At

the age of 42, he had to start a new career as an executive at a New York

advertising agency. Some writers attribute this ideological shift to his move

from academia to advertising:

Todd

(1994) noted that after Watson lost his academic post at Johns Hopkins, he

abandoned scientific restraint in favor of significantly increased stridency

and extremism, such that there were "two Watsons—a pre-1920, academic

Watson and a post-1920, postacademic Watson" (p. 167). Logue (1994) argued

that Watson's shift from an even-handed consideration of heredity and

environment to a position of bombast and extreme environmentalism was motivated

by the need to make money and the desire to stay in the limelight after he left

academia. (Rakos, 2013)

There

was another reason: the acrimonious debate in the mid-1920s over immigration,

particularly over whether the United States was receiving immigrants of dubious

quality. Rakos (2013) points to Watson's increasingly harsh words on eugenics

and the political background: "It is probably no coincidence that only in

the 1924 edition of the book—published in the same year that Congress passed

the restrictive Johnson-Lodge Immigration Act—did Watson express his belief

that behaviorism can promote social harmony in a world being transformed by

industrialization and the movement of peoples across the globe."

Eugenics

is mentioned, negatively, in his 1924 book:

But

you say: "Is there nothing in heredity-is there nothing in eugenics-[...]

has there been no progress in human

evolution?" Let us examine a few of the questions you are now bursting to

utter.

Certainly

black parents will bear black children [...]. Certainly the yellow-skinned

Chinese parents will bear a yellow skinned offspring. Certainly Caucasian

parents will bear white children. But these differences are relatively slight.

They are due among other things to differences in the amount and kind of

pigments in the skin. I defy anyone to take these infants at birth, study their

behavior, and mark off differences in behavior that will characterize white

from black and white or black from yellow. There will be differences in

behavior but the burden of proof is upon the individual be he biologist or

eugenicist who claims that these racial differences are greater than the

individual differences. (Watson, 1924, p. 76)

You

will probably say that I am flying in the face of the known facts of eugenics

and experimental evolution—that the geneticists have proven that many of the

behavior characteristics of the parents are handed down to the offspring—they

will cite mathematical ability, musical ability, and many, many other types. My

reply is that the geneticists are working under the banner of the old

"faculty" psychology. One need not give very much weight to any of

their present conclusions. (Watson, 1924, p. 79)

Conclusion

Antiracism

did not revive during the interwar years because of new data. Watson's shift to

radical environmentalism took place a half-decade after his departure from

academia. It was as an advertising executive, and as a crusader against the

1924 Immigration Act, that he entered the "environmentalist" phase of

his life. This phase, though poor in actual research, was rich in countless

newspaper and magazine articles that would spread his behaviorist gospel to a

mass audience.

The

same could be said for Franz Boas. He, too, made his shift to radical

antiracism when he was already semi-retired and well into his 70s. Although

this phase of his life produced very little research, it saw the publication of

many books and articles for the general public. As with Watson, the influence

of external political events was decisive, specifically the rise of Nazism in

the early 1930s.

In

both cases, biographers have tried to explain this ideological shift by

projecting it backward in time to earlier research. Boas' antiracism is often

ascribed to an early study that purported to show differences in cranial form

between European immigrants and their children (Boas, 1912). Yet Boas himself

was reluctant to draw any conclusions at the time, merely saying we should

"await further evidence before committing ourselves to theories that

cannot be proven." Later reanalysis found no change in skull shape once

age had been taken into account (Fergus, 2003). More to the point, Boas

continued over the next two decades to cite differences in skull size as

evidence for black-white differences in mental makeup (Frost, 2015).

Watson's

radical environmentalism has likewise been explained by his Little Albert

Experiment in 1920, an attempt to condition a fear response in an 11-month-old

child. Aside from the small sample size (one child) and the lack of any replication, it

is difficult to see how this finding could justify his later sweeping

pronouncements on environmentalism. There were admittedly other experiments,

but they came to an abrupt end with his dismissal from Johns Hopkins, and little

is known about their long-term effects:

Watson

tested his theories on how to condition children to express fear, love, or

rage—emotions Watson conjectured were the basic elements of human nature. Among

other techniques, he dropped (and caught) infants to generate fear and

suggested that stimulation of the genital area would create feelings of love.

In another chilling project, Watson boasted to Goodnow in summer 1920 that the

National Research Council had approved a children's hospital he proposed that

would include rooms for his infant psychology experiments. He planned to spend

weekends working at the "Washington infant laboratory." (Simpson,2000)

Watson

did apply behaviorism to the upbringing of his own children. The results were

disappointing. His first marriage produced a daughter who made multiple suicide

attempts and a son who sponged off his father. His second marriage produced two

sons, one of whom committed suicide (Anon, 2005). His granddaughter similarly

suffered from her behaviorist upbringing and denounced it in her memoir Breaking the Silence. Towards the end of

his life Watson regretted much of his child-rearing advice (Simpson, 2000).

References

Anon

(2005). The long dark night of behaviorism, Psych

101 Revisited, September 6

http://robothink.blogspot.ca/2005/09/long-dark-night-of-behaviorism.html

Boas,

F. (1912). Changes in the Bodily Form of Descendants of Immigrants, American Anthropologist, 14, 530-562.

Fergus,

C. (2003). Boas, Bones, and Race, May 4, Penn

State News

http://news.psu.edu/story/140739/2003/05/01/research/boas-bones-and-race

Frost,

P. (2015). More on the younger Franz Boas, Evo

and Proud, April 18

http://www.evoandproud.blogspot.ca/2015/04/more-on-younger-franz-boas.html

Rakos, R.F. (2013). John B. Watson's 1913 "Behaviorist Manifesto: Setting the stage for behaviorism's social action legacy, Revista Mexicana de analisis de la conducta, 39(2)

http://rmac-mx.org/john-b-watsons-1913-behaviorist-manifestosetting-the-stage-for-behaviorisms-social-action-legacy/

Simpson,

J.C. (2000). It's All in the Upbringing, John

Hopkins Magazine, April

http://pages.jh.edu/~jhumag/0400web/35.html

Watson,

J.B. (1919). Psychology from the

Standpoint of a Behaviorist,

http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2009-03123-000/

Watson,

J. B. (1924). Behaviorism. New York:

People's Institute.

http://books.google.ca/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=PhnCSSy0UWQC&oi=fnd&pg=PR10&dq=behaviorism+watson&ots=tW26oNvzjs&sig=YtDpYTYq3hE80QHJfo1Q4ebsuPI#v=onepage&q=behaviorism%20watson&f=false

4 comments:

Has anyone explained IQ differences as being on a continuum and that some groups seem to proceed further down the developmental phase (and take longer to mature?)

Wow. This guy sound like a real jerkface. Makes the Continuum Concept's recommendations look like hard science by comparison. His poor kids (and poor everyone else's kids.)

Since I am blacklisted at Unz Review, I will comment here. I just want to point out that a specific point of historical origin of anti-racism would have to be in Freemasonry. I point to the New Advent Catholic Online Encyclopaedia article on Masonry.

In it you have the research of Gruben who preserves Masonic teaching: This "universal religion of Humanity" which gradually removes the accidental divisions of mankind due to particular opinions "or religious", national, and social "prejudices", is to be the bond of union among men in the Masonic society, conceived as the model of human association in general.

"Humanity" is the term used to designate the essential principle of Masonry. [30] It occurs in a Masonic address of 1747. [31] Other watchwords are "tolerance", "unsectarian", "cosmopolitan".

Notice that it says to end "social prejudice". This should give you more things to research and the proper historical setting. Also look up Adam Weishpalt, the founder of the Illuminati, a sect within Masonry, who prophesized that nations and kings will disappear from the earth. Masonry gets its roots in the Kabbalah along with the Hermetic Tradition.

The roots of anti-racism is found in Jewish messianism that is carried by the Kabbalah which influenced many people starting in the Renaissance. That is the foundation.

I forgot to specifically mention that Gruben is referencing documents from 1737 and earlier!

Looking at John Watson's Wikipedia page, it ends with him burning his papers and his personal correspondence. Was Watson himself a Mason? Masonry was big in the early 1900s. He opposed the 1924 Immigration Act. That is an important clue. Was he a member of the Unitarian Church? All of these could have influenced his writings but looking at his Wikipedia page we run across John Dewey and Jacques Loeb who were his academic advisors; Dewey who laid the groundwork to organize the NAACP and Loeb is Jewish. Dewey was a fervent democraphile. The universalist message is certainly carried by democracy.

You can most certainly social engineer humans just like man has done to domestic animals. Man can make "the lion lie down with the lamb". Watson was converted to a pseudo-faith. Dewey called himself a socialist. Socialism is a carrier of Jewish Messianism and I'm sure that Watson was influenced either thru heretical Christian sects, Masonry or Socialism or all three. But we will never know for sure but having Dewey and Loeb as influences, there is a wiff of smoke.

Post a Comment