Human

brain size remained stable from 300,000 to 60,000 years ago. It then

diversified, becoming larger in some populations and smaller in others. This

was when modern humans were spreading out of Africa and into new environments

in Eurasia.

With

the end of the last ice age, some 10,000 years ago, northern hunting peoples

found themselves in a new environment. Men could no longer pursue herds of

wandering reindeer over the vast steppe-tundra. They now had to hunt over

shorter distances, and the game would be smaller and more varied. Meanwhile,

women now had opportunities for gathering fruits, berries, roots, and other

small food items. They thus turned toward food gathering, while men moved into

the formerly female domain of crafts, kiln operation, and shelter construction.

Cognitive demands were thus changing. Men no longer had to store huge amounts

of spatiotemporal data when tracking prey, and women were losing their dominance

of artisanal work (Frost 2019).

The

post-glacial period also brought an apparent decrease in brain size. Henneberg

(1988) found that male brains shrank by 9.9% and female brains by 17.4% between

the ice age and modern times. He attributed the decrease to a reduction in body

size. In a reanalysis of Henneberg's data, Hawks (2011) showed that the

reduction in body size explains only one-fifth to one-seventh of the decrease

in brain size. He also showed that the declining ratio of brain size to body

size did not affect all populations equally. In fact, it can be securely

demonstrated only for Europeans and Chinese. No decline is discernable for Nubians,

the only non-Eurasian population for which we have a large cranial sample.

In

a recent analysis of cranial data, DeSilva et al. (2021) argue that brain size

began to decrease with farming and the rise of larger, more complex societies.

They argue more specifically that the decrease was due to an increasing ability

to store knowledge externally either in written form (on tablets, paper, or

parchment) or in the brains of scribes, skilled tradesmen, and other knowledge

workers. People no longer had to rely solely on their own brains to store the

knowledge they needed:

[…]

the recent decrease in brain size may instead result from the externalization of

knowledge and advantages of group-level decision-making due in part to the

advent of social systems of distributed cognition and the storage and sharing

of information. (DeSilva et al. 2021, p. 1)

That

hypothesis has been challenged by Villmoare and Grabowski (2022). Because

farming was adopted at different times in different populations, they argue

that DeSilva et al. (2021) should have analyzed the cranial data on a regional

basis. But this was not done:

Since this transition [to farming]

occurred at different times across the globe, rather than over a single 3–5 ka

year period, under the hypothesis of DeSilva et al. (2021) we should

detect the change in different modern human populations at different times.

However, the dataset of DeSilva et al. (2021) is not organized to

test the hypothesis in this fashion. Populations from around the globe are

lumped together, with only 23 crania sampled over what we would argue to be a

critical window with regards to their hypothesis, 5–1 ka, and coming from

Algeria, England, Mali, China, and Kenya, among other locations. Later modern

human samples are focused on Zimbabwe (at 1.06 ka), the Pecos Pueblo sample

from the United States (1 ka), and finally, 165 crania (28% of the total

sample) are from Australian pre-Neolithic hunter-gatherer populations and dated

in DeSilva et al. (2021) to 100 years ago. (Villmoare and Grabowski

2022, p. 2)

The

cranial dataset suffers from other problems:

In that same dating category [100 years

ago], 307 (53% of the total sample) are from unspecified Morton Collection

crania, where we have no way of knowing how many may be from pre-Neolithic and

post-Neolithic populations. We also observe that the sample of DeSilva et al.

(2021) generates a modern human mean of 1,297 cc in the final 100-year

category, which is well below other published estimates of contemporary

world-wide modern mean human cranial capacity that range from ?1,340 cc up to

?1,460 cc. (Villmoare and Grabowski 2022, p. 2)

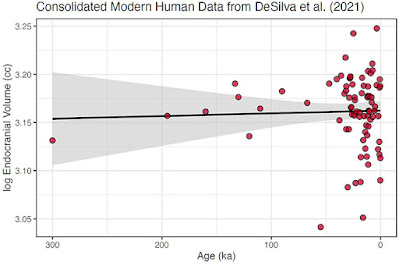

When

Villmoare and Grabowski (2022) reanalyzed the cranial data for the last 300,000

years, they found a very different picture:

[…] our analyses showed no changes in

brain size associated with the transition to agriculture during the Holocene.

Overall, our conclusion is that, given a dataset more appropriate to the

research question, human brain size has been remarkably stable over the last

300 ka. (Villmoare and Grabowski 2022, p. 4).

Actually, their reanalysis shows that brain size remained stable from 300,000 to 60,000 years ago. It then diversified, becoming larger in some populations and smaller in others. This was when modern humans were spreading out of Africa and into new environments in Eurasia (see chart at top of post).

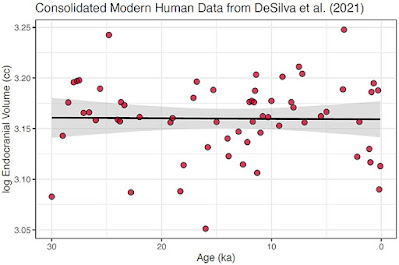

When

the authors looked more narrowly at the last 30,000 years, they found no

discernable change in mean brain size or in variation around the mean. They did

not attempt a regional analysis. That’s a pity because DeSilva et al. (2021)

may have been right within a more limited context, specifically that of complex

Eurasian societies. We still have John Hawks’ finding that brain size decreased

in Eurasians after the last ice age. But when exactly? Immediately after the

ice age? Or during the much later increase in social complexity?

Today,

more than a decade later, John Hawks has still not published that paper in a

journal. When I asked him why, he replied: "I did not feel it was

necessary to pursue formal journal publication for this, because I did not

think it fit well into the journals at the time." Yet, at that time, the

paper was exciting a lot of interest. This is what he wrote on his blog:

I've had a dozen requests from colleagues

to cite the paper (which anyone is welcome to do by using the arXiv number). I

also had two great interactions with colleagues who had comments and

suggestions on the preprint, which I am now incorporating into a revision.

(Hawks 2012)

He

might have had trouble publishing the paper in a top-tier journal. But the main

problem lay elsewhere. Once it got published, some academics might have viewed him

the wrong way. Perhaps not, but why take the risk? Why risk opportunities for

getting funding and invitations to work on big projects with big names?

Those

are questions that many anthropologists end up asking themselves. I have no

easy answer, other than to say that you can never control what other people think

of you. You only get to own your own thoughts, not those of others.

References

DeSilva,

J. M., Traniello, J. F. A., Claxton, A. G., and Fannin, L. D. (2021). When and

why did human brains decrease in size? A new change-point analysis and insights

from brain evolution in ants. Frontiers

in Ecology and Evolution 9: 742639. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.742639

Frost,

P. (2019). The Original Industrial Revolution. Did Cold Winters Select for

Cognitive Ability? Psych 1(1):

166-181. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych1010012

Hawks,

J. (2011). Selection for smaller brains in Holocene human evolution. arXiv:1102.5604 [q-bio.PE] https://arxiv.org/abs/1102.5604

Hawks, J. (2012). Spreading preprints in population biology. John Hawks Weblog, August 1. https://johnhawks.net/weblog/topics/meta/population-biology-arxiv-callaway-2012.html

Henneberg,

M. (1988). Decrease of human skull size in the Holocene. Human Biology 60: 395-405. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41464021

Villmoare,

B. and M. Grabowski. (2022). Did the transition to complex societies in the

Holocene drive a reduction in brain size? A reassessment of the DeSilva et al.

(2021) hypothesis. Frontiers in Ecology

and Evolution 10: 963568. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.963568

.jpg)