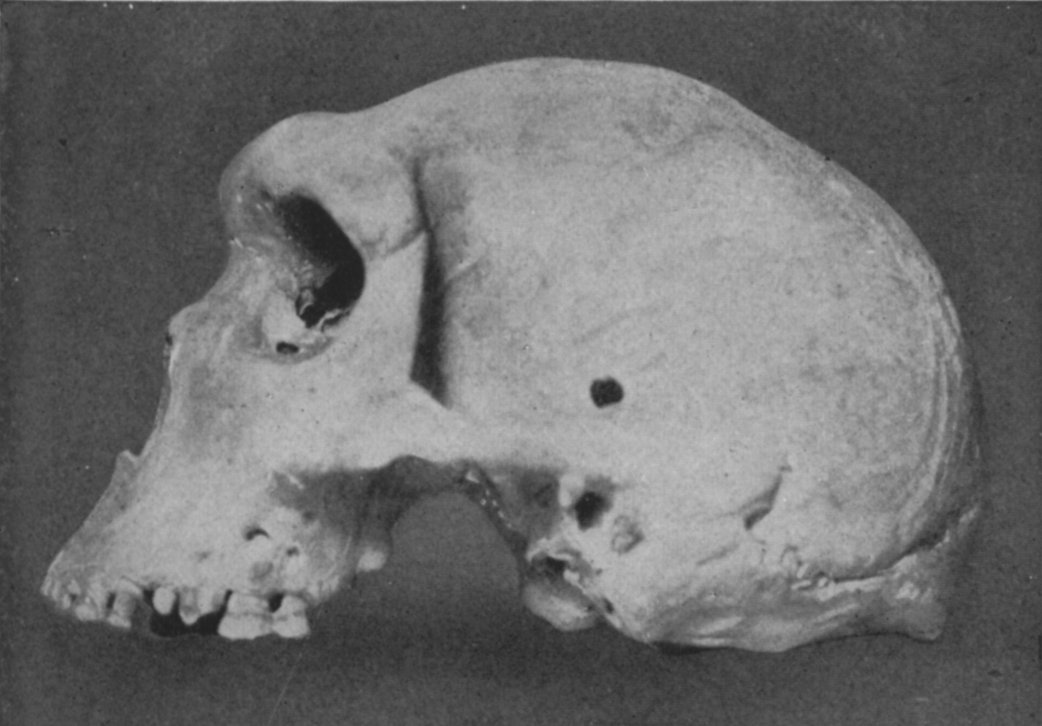

Skull

from Broken Hill (Kabwe), Zambia. This kind of human was still around when the

Neanderthals were going extinct in Europe. (Wikicommons)

East

Africa, 60,000 to 80,000 years ago. The relative stasis of early humans was

being shaken by a series of population expansions. The last one went global,

spreading out of Africa, into Eurasia and, eventually, throughout the whole

world (Watson et al., 1997). Those humans became us.

This

expansion took place at the expense of more archaic humans: Neanderthals in

Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia; Denisovans in East Asia; and

mysterious hobbit-like creatures in parts of Southeast Asia.

And

in Africa itself? We know less about those archaic humans, partly because the

archeological record is so patchy and partly because ancient DNA does not

survive as long in the tropics. Over time, the double helix breaks down, and

this decomposition occurs faster at higher ambient temperatures. We'll probably

never be able to reconstruct the genome of archaic Africans.

Yet

they did exist. Surprisingly, they held out longer in parts of Africa than

their counterparts did much farther away. A Nigerian site has yielded a skull

that is only about 16,300 years old and yet looks intermediate in shape between

modern humans on the one hand and Neanderthals and Homo erectus on the other. It resembles the skull of a very early

modern human, like the ones who once lived at Skhul and Qafzeh in Israel some

80,000 to 100,000 years ago (Harvati et al., 2011; Stojanowski, 2014).

Archaic

humans also held out in southern Africa. The Broken Hill or Kabwe skull, from

Zambia has been dated to 110,000 years ago and looks very much like a Homo erectus (Bada et al., 1974;

Stringer, 2011). This pre-sapiens human seems to have lasted into much later

times. Hammer et al. (2011) found that about 2% of the current African gene

pool comes from a population that split from ancestral modern humans some

700,000 years ago. They dated the absorption of this archaic DNA to about 35,000

years ago and placed it in Central Africa, since the level of intermixture is

highest in pygmy groups from that region.

Cognitive

modernity: less awesome on its home turf

Why

did archaic humans survive longer in Africa than elsewhere? Some of them were

more advanced than the Neanderthals or Denisovans, and perhaps better able to

fend off invasive groups. This was the case with archaic West Africans, who

seem to have been transitional between pre-sapiens and sapiens. They may have

met modern humans on a more level playing field while enjoying the home

team advantage.

On

the other hand, archaic southern Africans look clearly pre-sapiens. What

was levelling their playing field? Perhaps modern humans had advantages that

were more useful outside Africa. Klein (1995) has argued that this advantage

was cognitive, specifically a superior ability not only to create ideas but

also to share them with other individuals via language—in a word, culture. This

cognitive edge may have been more useful outside the tropics, where the yearly

cycle forced humans to plan ahead collectively and keep warm collectively by

building shelters and making garments. The result was a much wider range of human

technology: deep storage pits for meat refrigeration; hand-powered rotary

tools; kilns for ceramic manufacture; woven textiles; eyed sewing needles;

traps and snares; and so on (Frost, 2014).

Modern

humans were thus pre-adapted in Africa for later success elsewhere. We see this

in their rapid penetration of cold environments unlike anything in their place

of origin. By 43,500 years ago, they were already present in Central Europe at

a time when it was barren steppe with some boreal forest in sheltered valleys

(Nigst et al., 2014).

Pre-adaptation

is a recurring oddity of evolution. A new ability may initially be a bit

helpful and only later truly awesome. Does this mean that evolution anticipates

future success? Well, no. It's just that the difference between failure and

success—or between so-so success and the howling kind—often hinges on a few things

that may or may not exist in your current environment. By moving to other

environments, you increase your chances of finding one that will put your

talents to better use. Success is fragile, but so is failure.

References

Bada,

J.L., R.A. Schroeder, R. Protsch, & R. Berger. (1974). Concordance of

Collagen-Based Radiocarbon and Aspartic-Acid Racemization Ages, Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences (USA), 71, 914-917.

http://www.pnas.org/content/71/3/914.short

Frost,

P. (2014). The first industrial revolution, Evo

and Proud, January 18

http://evoandproud.blogspot.ca/2014/01/the-first-industrial-revolution.html

Hammer,

M.F., A.E. Woerner, F.L. Mendez, J.C. Watkins, and J.D. Wall. (2011). Genetic

evidence for archaic admixture in Africa, Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences (USA), 108, 15123-15128.

Harvati,

K., C. Stringer, R. Grün, M. Aubert, P. Allsworth-Jones, C.A. Folorunso.

(2011). The Later Stone Age Calvaria from Iwo Eleru, Nigeria: Morphology and

Chronology. PLoS ONE 6(9): e24024.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024024

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0024024

Klein,

R.G. (1995). Anatomy, behavior, and modern human origins, Journal of World Prehistory, 9,

167-198.

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02221838

Nigst,

P.R., P. Haesaerts, F. Damblon, C. Frank-Fellner, C. Mallol, B. Viola, M.

Gotzinger, L. Niven, G. Trnka, and J-J. Hublin. (2014). Early modern human

settlement of Europe north of the Alps occurred 43,500 years ago in a cold

steppe-type environment, Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences (USA), published online before print

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2014/09/16/1412201111.short

Stojanowski,

C.M. (2014). Iwo Eleru's place among Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene

populations of North and East Africa, Journal

of Human Evolution, epub ahead of print

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248414000876

Stringer,

C. (2011). The chronological and evolutionary position of the Broken Hill

cranium. American Journal of Physical

Anthropology, 144(supp. 52), 287

Watson,

E., P. Forster, M. Richards, and H-J. Bandelt. (1997). Mitochondrial footprints

of human expansions in Africa, American

Journal of Human Genetics, 61,

691-704. 0024024

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0024024

11 comments:

What about the infertility barrier?

The survival of archaic traits as late as 16,000 years ago in West Africa raises the obvious question of to what extent the Iwo Eleru population contributed to ancestry of today's West Africans. Might Eurasian back-migration have played a part in subsequent changes?

The fact the Y-DNA haplogroup E is so prevalent among Bantu-speaking peoples, and that an R1b variant can be found at high levels in parts of Cameroon, suggests that the answer is yes.

Back in the 1960s, Carleton Coon, in "The Living Races of Man," suggested that modern black Africans were morphologically intermediate between Pygmies and Mediterranean populations. He further theorized that African populations could be arranged in a spectrum from those who derived most of their ancestry from Eurasians (like Egyptians and Berbers)to those descended mostly from the original inhabitants (Pygmies and Bushmen), with groups like Ethiopians, Nilo-Saharans, and Bantus falling at various points in between.

Coon was wrong about a lot of things, but this idea may have been one of his more prescient insights.

If the tropics are/were a particularly harsh selective environment but at the same time generate a lot of genetic mutation then Africans would end up with increasing amounts of neutral dna

But dna that is neutral inside the region where it develops isn't necessarily neutral outside that area.

So you could imagine a situation where Africans pick up more and more neutral dna over time then every interstitial some move out of Africa and die out with the next ice age until eventually one of those bits of neutral junk dna (aka spare part dna) turns out to be very beneficial *outside* the tropics allowing them to survive the next cold phase.

"Success is fragile, but so is failure.

"

I'll remember that.

Another factor that likely helped pre sapiens survive quite late in certain parts of Africa is tropical diseases. New comers would be less adapted to the local diseases. And a disease heavy environment selects more for fast breeding R traits than K traits.

Dumbnonymous said...

"The survival of archaic traits as late as 16,000 years ago in West Africa raises the obvious question of to what extent the Iwo Eleru population contributed to ancestry of today's West Africans. Might Eurasian back-migration have played a part in subsequent changes?"

What Eurasian back-migration?

Dumbnonymous said...

"The fact the Y-DNA haplogroup E is so prevalent among Bantu-speaking peoples, and that an R1b variant can be found at high levels in parts of Cameroon, suggests that the answer is yes."

Y-DNA HG E clearly arose in Africa. All the diversity and frequency points to Africa and nowhere else.

Dumbnonymous said...

"Back in the 1960s, Carleton Coon, in "The Living Races of Man," suggested that modern black Africans were morphologically intermediate between Pygmies and Mediterranean populations. He further theorized that African populations could be arranged in a spectrum from those who derived most of their ancestry from Eurasians (like Egyptians and Berbers)to those descended mostly from the original inhabitants (Pygmies and Bushmen), with groups like Ethiopians, Nilo-Saharans, and Bantus falling at various points in between."

Carlteon Coon was mostly a hack that knew nothing of genetics. also you don't know much about genetics either.

1. Central African pygmies aren't that old nor are they the original inhabitants of Africa.

2. Nilotic Nilo-Saharans actually have more Y-DNA HG A & B as well as Mt-DNA HG L0, L1 and L2 than both Pygmies and Khoisan yet Nilotes have more Eurasian affinity.

Dumbnonymous said...

"Coon was wrong about a lot of things, but this idea may have been one of his more prescient insights."

Nope! He was a hack!

Anon,

If there had been an infertility barrier between moderns and archaics, it must have been partial at best. We see Neadnerthal admixture in modern Eurasians.

Anon,

According to Watson et al. (1997), about 13% of the sub-Saharan gene pool comes from a demic expansion about 111,000 years ago that corresponds to the entry of Skhul-Qafzeh hominins into the Middle East. Given the similarities between Iwo Eleru and Skhul-Qafzeh, I suspect that this 13% comes from archaic humans like those at Iwo Eleru.

So sub-Saharan Africans have a higher level of archaic admixture than do Eurasians, but most of this admixture seems to have come from people who were on the threshold of modernity.

Anon,

Except that the demographic expansion began in Africa. This wasn't a neutral trait inside Africa. It was already having adaptive consequences.

Luke Lea,

It came to me during my last rewrite of that post. I was trying to sum up my main idea in as few words as possible.

Dumb,

Calling people you don't like is intellectual laziness. It eliminates the effort of trying to come up with a coherent counter-argument.

@PF

"Except that the demographic expansion began in Africa. This wasn't a neutral trait inside Africa. It was already having adaptive consequences."

Yes, I didn't state it fully. I think it will turn out that "out of the tropics" was the big step and out of Africa relatively minor in comparison.

(With that "out of the tropics" population getting mostly squished in the interim by a mixture of back migration and Bantu expansion.)

"With that "out of the tropics" population getting mostly squished..."

by that i mean the distinctively African segment of the "out of the tropics" population.

If the Iwo Eleru people contibuted 13 percent of the modern West African gene pool, where were the people who contributed the other seven-eights of it located 16,000 years ago? And when did they come into tropical West Africa and absorb their predecessors? Can genetics and/or fossil finds elsewhere on the African continent provide clues? I know Hammer et. al. were able to estimate 35,000 BP for the 2% absorption of the very archaic lineage. But what about these quasi/almost-modern folks?

Unfortunately, the archaeological record is very spotty in West Africa (and sub-Saharan Africa in general). I suspect that the Iwo Eleru people survived until very recent times, perhaps into the Holocene. There are legends in West Africa of an earlier people (who are said to have been lighter-skinned).

Post a Comment