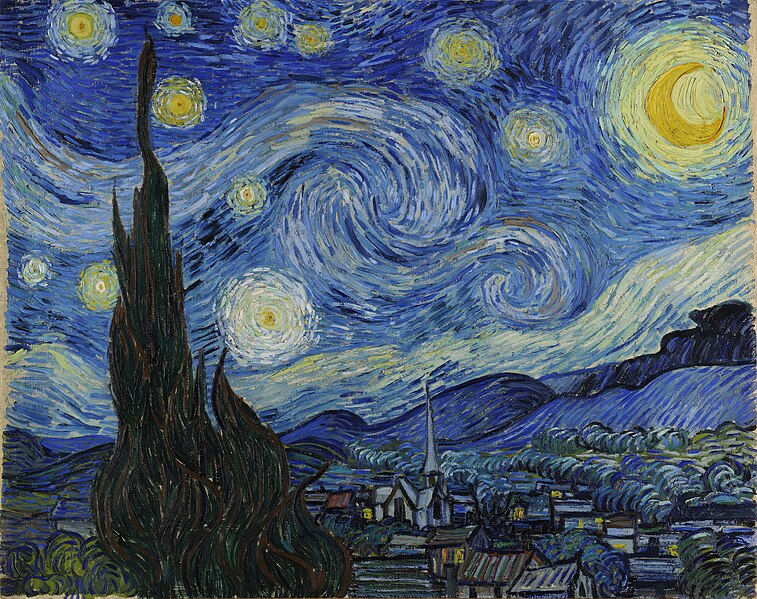

The Starry Night, Vincent

van Gogh (1853-1890).

The more you empathize with the world, the more you feel its joy and pain, but

too much can lead to overload.

One

of my interests is affective empathy, the involuntary desire not only to

understand another person's emotional state but also to make it one's own—in

short, to feel the pain and joy of other people. This mental trait has a

heritability of 68% and is normally distributed along a bell curve within any

one population (Chakrabarti and Baron-Cohen, 2013). Does it also vary

statistically among human populations? This is possible. Different cultures

give varying importance to affective empathy, and humans have adapted much more

to their cultural environments than to their natural environments. This is why

human genetic evolution accelerated over 100-fold about 10,000 years ago when

humans began to abandon hunting and gathering for farming, which in turn led to

increasingly diverse forms of social organization (Hawks et al., 2007).

I

have argued previously that Europeans to the north and west of the Hajnal Line

(an imaginary line running from Trieste to Saint-Petersburg) have adapted to a

cultural environment of weaker kinship and, conversely, greater individualism. In

such an environment, the reciprocal obligations of kinship are insufficient to

ensure compliance with social rules. This isn’t a new situation. Weak kinship is

inherent to the Western European Marriage Pattern, which goes back to at least

the 12th century, if not earlier.

This

cultural environment has selected for a package of mental adaptations:

-

capacity to internalize punishment for disobedience of social rules (guilt

proneness)

-

capacity to simulate and then transfer to oneself the emotional states of

people who may be affected by rule-breaking (affective empathy)

-

desire to seek out and expel rule-breakers from the moral community

(ideological intolerance).

The

above mental package has enabled Northwest Europeans to free themselves from

the limitations of kinship and organize their societies along other lines,

notably the market economy, the modern State, and political ideology. They have

thus managed to meet the threefold challenge of creating larger societies,

ensuring greater compliance with social rules, and making possible a higher level of

personal autonomy.

So

much for the theory. What direct evidence do we have that affective empathy is

stronger on average in Northwest Europeans? We know that a higher capacity for

affective empathy is associated with a larger amygdala, which seems to control our

response to facial expressions of fear and other signs of emotional distress

(Marsh et al., 2014). Two studies, one American and one English, have found

that "conservatives" tend to have a larger right amygdala (Kanai et al., 2011; Schreiber et al., 2013). In both cases, my hunch is that

"conservatives" are disproportionately drawn from populations that

have, on average, a higher capacity for affective empathy.

But

testing this kind of hunch would require a large-scale comparative study, which

in turn would require cutting up a lot of cadavers or doing a lot of MRIs. It

would be nicer to have a genetic marker that shows up on a simple test. It

would also be cheaper.

We

may now have that marker: a deletion variant of the ADRA2b gene. Carriers remember emotionally arousing images more

vividly and for a longer time, and they also show more activation of the

amygdala when viewing such images (Todd and Anderson, 2009; Todd et al., 2015).

This is not to say that the ADRA2b

deletion variant is the sole reason or even the major reason why some people

have increased capacity for affective empathy. As with intelligence, an increase

in capacity seems to have come about through changes of small effect at many

genes.

Nor

can we say that "emotional memory" is equivalent to affective

empathy. Instead, it seems to be one component, albeit a critical one: the

capacity to imagine an emotional state based on visual information (a picture

of a person's face, a puppy dog, etc.) and then keep it as part of one's

current emotional experience. Emotional memory may be upstream to affective empathy,

being perhaps closer to cognitive empathy—the ability to imagine how another

person feels without involuntarily making that feeling one's own.

Does its incidence

differ among human populations?

This

variant was first studied in the United States. Small et al. (2001) found a

higher incidence in Caucasians (31%) than in African Americans (12%). Belfer et al. (2005) likewise found a higher incidence in Caucasians (37%) than in

African Americans (21%).

In

a press release, the authors of the latest study noted that this variant is not

equally common in all humans:

The

ADRA2b deletion variant appears in

varying degrees across different ethnicities. Although roughly 50 per cent of

the Caucasian population studied by these researchers in Canada carry the

genetic variation, it has been found to be prevalent in other ethnicities. For

example, one study found that just 10 per cent of Rwandans carried the ADRA2b gene variant. (UBC News, 2015)

Curiously,

its incidence seems higher among “Canadian Caucasians” (50%) than among

"American Caucasians” (31-37%). This may reflect differences in

participant recruitment or in ethnic mix between the two countries. Indeed, the

"Caucasian" category may prove to be problematic because it includes

people from both sides of the Hajnal Line. If the average incidence is 31% to

50%, there may be populations that score much higher.

I

have found only three studies on specific European ethnicities. The first study

found an incidence of 50% in Swiss participants (de Quervain, 2007). The second

one found an incidence of 56% in Dutch participants (Cousijn et al., 2010). The

third one had two groups of participants: Israeli Holocaust survivors and a

control group of European-born Israelis who had emigrated with their parents to

the British Mandate of Palestine. The incidence was 48% in the Holocaust

survivors and 63% in the controls (Fridman et al., 2012).

From

East Asia, a study on Chinese participants reported an incidence of 68% (Zhang et al., 2005). This is surprising because Chinese seem less likely to

distinguish between cognitive empathy and affective empathy (Siu and Shek,2005). Japanese participants had an incidence of 56% in one study (Suzuki et al., 2003) and 71% in another (Ishii et al., 2015). Among the Shors, a Turkic

people of Siberia, the incidence was 73%. Curiously, the incidence was higher

in men (79%) than in women (69%). It may be that male non-carriers had a higher

death rate, since the incidence increased with age (Mulerova et al., 2015).

Conclusion

The

picture is still incomplete but the incidence of the ADRA2b deletion variant seems to range from a low of 10% in some

sub-Saharan African groups to a high of 50-65% in some European groups and

55-75% in some East Asian groups. Given the high values for East Asians, I

suspect this variant is not a marker for affective empathy per se but rather

for empathy in general (cognitive and affective).

It

may be significant that a high incidence was found among the Shors, who were

largely hunter-gatherers until recent times. This suggests that empathy reached

high levels in Eurasia long before the advent of complex societies, or even

farming. The example of the Shors also suggests that non-carriers of the

deletion variant suffer from higher mortality—a somewhat surprising finding,

given the evidence that carriers have a higher risk of heart disease.

More

research is needed on how this variant interacts with variants at other genes.

For instance, it has been found that people with at least one copy of the short

allele of 5-HTTLPR tend to be too

sensitive to negative emotional information. This effect seems to be attenuated

by the deletion variant of ADRA2b,

which either keeps one from dwelling too much on a bad emotional experience or

helps one anticipate and prevent repeat experiences (Naudts et al., 2012).

Nonetheless, too much affective empathy may lead to an overload where one ends

up helping others to the detriment of oneself and one’s family and kin.

References

Belfer,

I., B. Buzas, H. Hipp, G. Phillips, J. Taubman, I. Lorincz, C. Evans, R.H.

Lipsky, M.-A. Enoch, M.B. Max, and D. Goldman. (2005). Haplotype-based analysis

of alpha 2A, 2B, and 2C adrenergic receptor genes captures information on

common functional loci at each gene. Journal

of Human Genetics, 50, 12-20.

http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mary_Anne_Enoch/publication/8134892_Haplotype-based_analysis_of_alpha_2A_2B_and_2C_adrenergic_receptor_genes_captures_information_on_common_functional_loci_at_each_gene/links/02e7e53559c67a2c02000000.pdf

Chakrabarti,

B. and S. Baron-Cohen. (2013). Understanding the genetics of empathy and the

autistic spectrum, in S. Baron-Cohen, H. Tager-Flusberg, M. Lombardo. (eds). Understanding Other Minds: Perspectives from

Developmental Social Neuroscience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

http://books.google.ca/books?hl=fr&lr=&id=eTdLAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA326&ots=fHpygaxaMQ&sig=_sJsVgdoe0hc-fFbzaW3GMEslZU#v=onepage&q&f=false

Cousijn,

H., M. Rijpkema, S. Qin, H.J.F. van Marle, B. Franke, E.J. Herman, G. van

Wingen, and G. Fernández. (2010). Acute stress modulates genotype effects on

amygdala processing in humans. Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A., 107, 9867-9872.

http://www.pnas.org/content/107/21/9867.full.pdf

de Quervain, D.J. F., I.-T.

Kolassa, V. Ertl, L.P. Onyut, F. Neuner, T. Elbert, and A. Papassotiropoulos. (2007). A deletion

variant of the alpha2b-adrenoceptor is related to emotional memory in Europeans

and Africans. Nature Neuroscience, 10, 1137-1139.

Fridman,

A., M.H. van IJzendoorn, A. Sagi-Schwartz, and M.J. Bakermans-Kranenburg.

(2012). Genetic moderation of cortisol secretion in Holocaust survivors: A

pilot study on the role of ADRA2B. International

Journal of Behavioral Development. 36,

79

http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Abraham_Sagi-Schwartz/publication/230887396_Genetic_moderation_of_cortisol_secretion_in_Holocaust_survivors__A_pilot_study_on_the_role_of_ADRA2B/links/0912f505c75bb4a01d000000.pdf

Hawks,

J., E.T. Wang, G.M. Cochran, H.C. Harpending, and R.K. Moyzis. (2007). Recent

acceleration of human adaptive evolution. Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences (USA), 104, 20753-20758.

http://harpending.humanevo.utah.edu/Documents/accel_pnas_submit.pdf

Ishii,

M., H. Katoh, T. Kurihara, and S. Shimizu. (2015). Catechol-O-methyl

transferase gene polymorphisms in Japanese patients with medication overuse

headaches. JSM Genetics and Genomics,

2(1), 1-4.

http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Masakazu_Ishii/publication/273587694_Catechol-O-methyl_transferase_gene_polymorphisms_in_Japanese_patients_with_medication_overuse_headaches/links/5507e87a0cf26ff55f7f719d.pdf

Kanai,

R., T. Feilden, C. Firth, and G. Rees. (2011). Political orientations are

correlated with brain structure in young adults. Current Biology, 21, 677

- 680.

http://www.cell.com/current-biology/abstract/S0960-9822(11)00289-2

Marsh,

A.A., S.A. Stoycos, K.M. Brethel-Haurwitz, P. Robinson, J.W. VanMeter, and E.M.

Cardinale. (2014). Neural and cognitive characteristics of extraordinary

altruists. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, 111,

15036-15041.

http://www.pnas.org/content/111/42/15036.short

Mulerova,

T.A., A.Y. Yankin, Y.V. Rubtsova, A.A. Kuzmina, P.S. Orlov, N.P. Tatarnikova,

V.N. Maksimov, M.I. Voevoda, and M.Y. Ogarkov. (2015). Association of ADRA2B

polymorphism with risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in native population

of mountain Shoria. Bulletin of Siberian

Medicine, 14, 29-34.

Naudts,

K.H., R.T. Azevedo, A.S. David, K. van Heeringen, and A.A. Gibbs. (2012).

Epistasis between 5-HTTLPR and ADRA2B polymorphisms influences attentional bias

for emotional information in healthy volunteers. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 15, 1027-1036.

Schreiber,

D., Fonzo, G., Simmons, A.N., Dawes, C.T., Flagan, T., et al. (2013). Red

Brain, Blue Brain: Evaluative Processes Differ in Democrats and Republicans. PLoS ONE, 8(2): e52970.

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0052970

Siu,

A.M.H. and D.T. L. Shek. (2005). Validation of the Interpersonal Reactivity

Index in a Chinese Context. Research on

Social Work Practice, 15,

118-126.

http://rsw.sagepub.com/content/15/2/118.short

Small,

K.M., and S.B. Liggett. (2001) Identification and functional characterization

of alpha(2)-adrenoceptor polymorphisms. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 22,

471-477.

Suzuki N, Matsunaga T,

Nagasumi K, Yamamura T, Shihara N, Moritani T, et al. (2003). a2B adrenergic receptor deletion polymorphism

associates with autonomic nervous system activity in young healthy Japanese. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology &

Metabolism, 88, 1184-1187.

http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tetsuro_Matsunaga/publication/10863380_Alpha(2B)-adrenergic_receptor_deletion_polymorphism_associates_with_autonomic_nervous_system_activity_in_young_healthy_Japanese/links/00b7d530379a0f06bf000000.pdf

Todd,

R.M. and A.K. Anderson. (2009). The neurogenetics of remembering emotions past.

Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences U.S.A., 106, 18881-18882

http://www.pnas.org/content/106/45/18881.short

Todd,

R.M., M.R. Ehlers, D. J. Muller, A.

Robertson, D.J. Palombo, N. Freeman, B. Levine, and A.K. Anderson (2015).

Neurogenetic Variations in norepinephrine availability enhance perceptual

vividness. The Journal of Neuroscience,

35, 6506-6516.

UBC

News. (2015). How your brain reacts to emotional information is influenced by

your genes, May 6

http://news.ubc.ca/2015/05/06/how-your-brain-reacts-to-emotional-information-is-influenced-by-your-genes/

Zhang,

H., X. Li, J. Huang, Y. Li, L. Thijs, Z. Wang, X. Lu, K. Cao, S. Xie, J.A.

Staessen, J-G. Wang. (2005). Cardiovascular and metabolic phenotypes in

relation to the ADRA2B insertion/deletion polymorphism in a Chinese population.

Journal of Hypertension, 23, 2201-2207.

http://www.staessen.net/publications/2001-2005/05-30-P.pdf

3 comments:

There's a significant difference between American whites and Canadian whites. As you probably know American whites are more likely to hold extremist or right-wing views... and to vote for Donald Trump. "We'll send drones to kill all the illegal immigrants" and "Mexicans are rapists and murderers" is the rhetoric emanating from American whites, such as Donald Trump and his followers. I doubt that these whites are overburdened with too much empathy, to be honest.

BTW, since you've written a lot on IQ in whites vs. other races, could you explain why white Americans (a supposedly high-IQ population) love Trump and are prepared to vote for him, a low-IQ man who can't form a coherent sentence, talks like a 3rd-grader according to analysts, and only knows words like "stupid" and "bad" ? He leads by double digits in the mostly-white Republican party. Even Jeb Bush, a far higher-IQ man, isn't faring too well with white Republicans. But I thought the white population had a high IQ, was intelligent, and would have preferred someone on their level.

Reader,

He's the only candidate addressing the immigration issue.

Heh. Expert neg.

Post a Comment