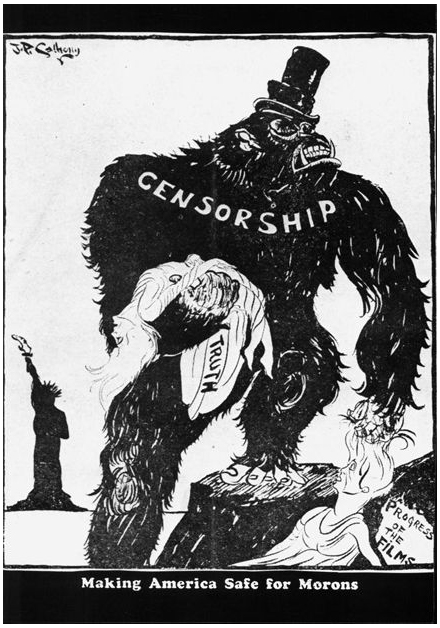

The Film Mercury, 1926

(Wikicommons) – When the mob decides truth.

Until recently, it was almost

impossible to remove an article from the published scientific literature. You

would have to ask each university library for permission to go to the stacks

and tear it out from a bound volume. Your request would almost certainly be denied.

All of that has changed with

online publishing. Now, you only need permission from the publishing company,

and removal is just a click away. The ease of online removal can lead to abuse,

as noted back in 2005:

Before the advent of electronic journals, it was very hard for publishers to purge articles from their journals. At best, they could publish a later retraction. [...]

Now, however, with publishers controlling their own digital archives, and print copies no longer being produced, it has proven to be entirely too easy for some publishers to purge these archives of unwanted articles, much to the dismay of those who, like me, fear for the long-term integrity and trustworthiness of the published record of science and our intellectual heritage. In addition, if such materials can be removed, it often means they can be modified after publication as well.

Elsevier, for example, has removed about 30 articles so far from its ScienceDirect journal article archive, just since the year 2000, for various reasons. [...] The fear that many of us have is that individuals, corporate entities, and even governments, including ours, will begin to use such techniques to control the published record for political purposes or in order to cover up embarrassing information. (Davidson 2005)

That fear has come true with

the removal of a paper by J. Phillippe Rushton and Donald Templer from the

psychology journal Personality and

Individual Differences. Rushton is known for his belief that cognitive

ability varies not only between individuals but also between human populations.

That was not, however, the subject of the removed paper. The subject was body

coloration, specifically the fact that darker animals tend to be larger, more

polygynous, and more aggressive. This correlation seems to hold true not only

between species but also within species.

I believe such a correlation

exists, but it’s not a simple one of cause and effect (see my last post). In

any case, my opinion doesn’t matter. What matters is the right of all

researchers to present their findings and interpretations in the scientific

literature. If errors are made, others will point them out. That’s how the

system works.

Unfortunately, that’s not how

some people want the system to work. Rushton had enemies, and they now see an

opportunity to destroy his legacy, much of it being papers he published in

Elsevier journals. I suspect they identified the above paper as the easiest

target for removal, a kind of “test case.” It’s not about human cognition and

is viewed with skepticism even by Rushton’s defenders, who seem to have fallen

back to a defense line around his IQ work. Pauvres

naïfs.

Demands for removal began a

year ago, but it was really the events of the last month that made the journal

give in.

My email exchange

Initially, I wasn't sure who

authorized the removal. Was it Elsevier, i.e., the publisher? Or was it the

current editor of Personality and

Individual Differences? I emailed the latter, Don Saklofske, partly to

protest this decision and partly to confirm he had been responsible. The

following is my email exchange with him and with Elsevier:

Dear

Dr. Saklofske:

I

am writing with regard to your decision to remove the 2012 article by J.

Philippe Rushton and Donald Templer from your journal. This is an unusual move and breaks with

longstanding practice. Once an article has passed peer review and been

published, it remains in the scientific literature even if subsequently proven

wrong. There have been a few cases of articles being withdrawn shortly after

publication, but there have been no cases, until now, of an article being

removed eight years later.

My

personal judgment of this article is like that of many articles I read. I agree

with parts of it and disagree with others. It is true that darker-colored

animals tend to be larger and more aggressive, this being true not only between

species but also within species. We can disagree about the causes, but the

correlation is real and has been confirmed by other researchers.

I

could argue this point at greater length, but I shouldn't have to. None of us

has the right to sit in judgment on an article that is already established in

the scientific literature. If one disagrees with an article, one is always free

to write down one's criticisms and submit them for publication to the journal

in question, but no one has the right to "unpublish" an existing

article, however much one disagrees with it.

I

urge you to reconsider your decision. You have created a dangerous precedent.

Yours

sincerely,

Peter

Frost

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Hello

Peter... thank you for your email.

Indeed this was a difficult and challenging investigation and resulting

decision that began last year but for which the controversy had been ongoing

even before I became editor of PAID. I

am forwarding your letter to Catriona Fennell, Director of Publishing Services

at Elsevier, who would have a much greater knowledge of the timelines on

retracted articles following publication.

Sincerely

don

D.H.

Saklofske, Ph.D

Editor:

PAID

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Don,

Perhaps

I am mistaken. Was this your decision or was it Elsevier's? In other words, who

actually made the decision and who will take responsibility for it?

Sincerely,

Peter

Frost

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Hello

Peter... decisions related to

corrigendums, letters of concern/warning, and retractions 'rests with the

editor'! I along with a panel of PAID

Sr. Associate Editors comprised the signatories who reviewed the 'evidence'

resulting in the decision to retract the Rushton and Templer article.

This

was NOT Elsevier's decision; their office was consulted and advised of our

investigation and actions only because they are the owners and publishers of

the journal and it was important that I then understand their position on such

matters re. legal and ethical guidelines. However I also thought you were also

raising the point of 'time between publication to retraction' and this might be

better known by the publisher of PAID and many other journals across varying

disciplines. Should I have misunderstood, I apologize and withdraw my previous

request to Elsevier.

Lastly, retraction of journal articles is not so uncommon (e.g. see Brainard and

You; www.sciencemag.org › news › 2018/10 ›) and while the time from publication

to retraction is usually less than 8 years, we began our examination of this

paper last year (2019) following increased concerns from the scientific community,

and two years after my appointment as editor.

Thank

you for sharing your comments and viewpoint.

don

D.H.

Saklofske, Ph.D

Editor:

PAID

cc. Elsevier: Catriona Fennell and Gail Rodney

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Dear

Dr Frost,

Thank

you for your comments, we appreciate that there are a variety of views on how

the literature should be corrected.

Since

2009, the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) guidelines (updated in 2019)

have recommended retraction for cases where misconduct has taken place, but

also in cases of error:

"Journal

editors should consider retracting a publication if:

•

they have clear evidence that the findings are unreliable, either as a result

of misconduct (e.g. data fabrication) or honest error (e.g. miscalculation or

experimental error)"

https://publicationethics.org/files/u661/Retractions_COPE_gline_final_3_Sept_09__2_.pdf

Elsevier

journals endorse these guidelines from COPE and put them into practice, as do

most major publishing houses. Analysis

by Retraction Watch, who have compiled a database of >18,000 retractions,

found that at least 40% of retractions were due to error rather than to fraud:

https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/10/what-massive-database-retracted-papers-reveals-about-science-publishing-s-death-penalty

However,

it is likely that retractions due to misconduct receive more amount of

attention in the media and community.

It

is not particularly unusual for older papers to be retracted, please see below

some examples of retractions from Elsevier journals several years after

publication, in one case a 1985 paper being retracted in 2013. More data is

available, also from other publishing houses, from the Retraction Watch

database: http://retractiondatabase.org/

Sincerely

yours,

Catriona

Fennell

Director

Publishing Services

STM

Journals

Elsevier

Radarweg

29, 1043NX Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dear

Catriona Fennell,

I

looked through the examples of retractions you provided. All of them concern

papers in engineering or the medical sciences. Most of them were retracted

because the same material had been published elsewhere, either by the same

author (duplication) or by another author (plagiarism). There were a few other

reasons:

-

Paper retracted at author's request

-

Fabrication or falsification of data

-

Inability to confirm authorship of the paper and inability to interrogate the

data presented in the paper

None

of these examples resembles the retraction of the paper by J. Philippe Rushton

and Donald Templer. That paper was in the social sciences, and there was no

duplication or plagiarism involved. Nor do any of the other reasons apply. The

reason seems to be more ideological. Am I right?

Sincerely,

Peter

Frost

Conclusion

There were no further replies

from Catriona Fennell or Don Saklofske. Perhaps they consider the case closed.

They did prove me wrong on one point: several longstanding articles have

already been removed from the scientific literature. The record is a paper

published in 1999 and removed in 2019. Removal was justified on the following

grounds:

Despite contact with Futase Hospital and Kurume University in place of the co-authors, who could not be located, the Journal was unable to confirm whether ethical approval had been granted for this study and has been unable to confirm the authorship of this paper. The Journal was also unable to interrogate the data presented in this paper as no records have remained of this study. This constitutes a violation of our publishing policies and publishing ethics standards.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S8756328298001859?via%3Dihub

After twenty years it’s often

difficult to locate the authors of a paper, especially if they are grad

students. Their academic affiliation has changed or they may have left academia

entirely. Even if they can be located, they may no longer have the raw data to

support their findings. My PhD data files are on floppy disks. How can I read

them today? And would they still be readable?

So if you dislike a scientific

paper, and if its authors are no longer available, you can get rid of it by

making a plausible accusation. Who is going to prove you wrong? This is another

kind of abuse alongside the political and ideological one. "Science" increasingly

belongs to established researchers with secure positions and access to legal

assistance. Yet, historically, most innovative research has been done by individuals

working alone with little institutional support. Charles Darwin was a country

squire with no academic affiliation. Albert Einstein published major papers

while working at a patent office. Intellectual breakthroughs tend to be made by

outsiders.

Outsiders are losing their

place in the academic community, especially ideological outsiders. This may be

one reason why scientific and technological progress is slowing down. Indeed, such

progress may sow the seeds of its destruction by creating better ways to manage

information. And people.

But there’s another reason why

outsiders are being squeezed out of academia. During the late 20th century,

Christianity could no longer control what people said and believed, but it was

still strong enough to keep other belief systems from taking over and imposing

their controls. That happy interregnum is over. We’re moving into an intellectual

environment where insiders are no longer interested in finding truth. They want

to decide truth. To that end, they want to decide who gets published and who remains published. If you fall

out of favor, they may delete all of your publications, and you will cease to

exist as an intellectual entity. You’ll be unpersoned.

A few words to the journal editor

Don Saklofske,

You have created a precedent,

and we’ll see more of these “removals.” I suspect you realize the gravity of

your decision but feel you had no choice. Such a decision must be especially

difficult for you, an evolutionary psychologist who has worked on genetic

determination of cognition, impulsiveness, and empathy. Your research

interests, however, have to be weighed against the treatment you’ve seen meted

out to certain academics, including some at your university. Why share their

fate?

So you had no choice. Anyway,

someone else would have done the same thing sooner or later.

And, anyway, J. Philippe

Rushton was a racist, like those Confederate generals whose statues have been

torn down and taken away.

Apparently, Rushton is like a

lot of people nowadays, such as Christopher Columbus, George Washington, Thomas

Jefferson, and Sir John A. Macdonald. Of course, you’re not like those people

either. Your name is further down the list, and it’s not a statue that will disappear

when your time comes.

So remember: the more you give

in now, the more you’ll have to give in later. At best, you’re buying yourself

time, and not as much as you think.

References

Davidson, L.A. (2005). The End

of Print: Digitization and Its Consequence-Revolutionary Changes in Scholarly

and Social Communication and in Scientific Research. International Journal of Toxicology 24(1): 25-34

Rushton, J. P., and D.I.

Templer. (2012). Do pigmentation and the melanocortin system modulate

aggression and sexuality in humans as they do in other animals? Personality and Individual Differences 53(1):

4-8